Artist

Believe it or Not, 2020-2021

SHELLIE

ZHANG

Believe it or Not explores the politics of believability for stories outside of the dominant, nostalgized, and romanticized settler imagination. The series, loosely referencing the board game Clue, is comprised of six colour-coded images accompanied by matching archival materials. Zhang’s works reflect on the mythos, visuals and sites of historical re-enactments while considering their effectiveness, intended audience, and role in prevailing historical narratives. Believe it or Not pays tribute to the ability of Chinese communities in Western Canada to make space in unwelcoming cities and challenges the colonial narratives that contribute to misconceptions of truth.

Believe

it or Not

Believe it or Not explores the politics of believability for stories outside of the dominant, nostalgized, and romanticized settler imagination. The series, loosely referencing the board game Clue, is comprised of six colour-coded images accompanied by matching archival materials. Zhang’s works reflect on the mythos, visuals and sites of historical re-enactments while considering their effectiveness, intended audience, and role in prevailing historical narratives. Believe it or Not pays tribute to the ability of Chinese communities in Western Canada to make space in unwelcoming cities and challenges the colonial narratives that contribute to misconceptions of truth.

Believe it or Not

SHELLIE ZHANG

Believe it or Not, 2020-2021

HELP WANTED

The Curious Case of

Quong Wing v. R

Exhibit A (The Curious Case of Quong Wing v. R)(purple),

2020-2021, Archival Inkjet Print, 18x24”

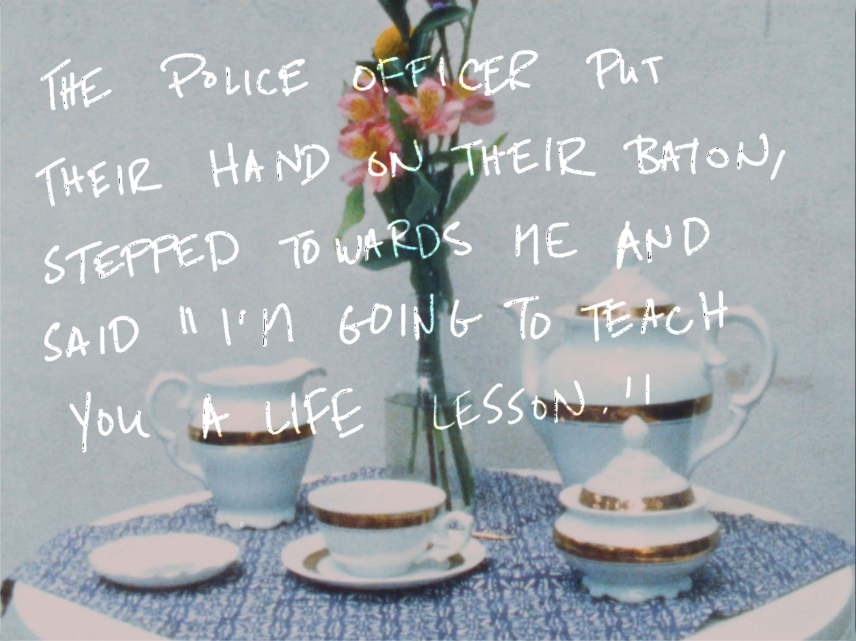

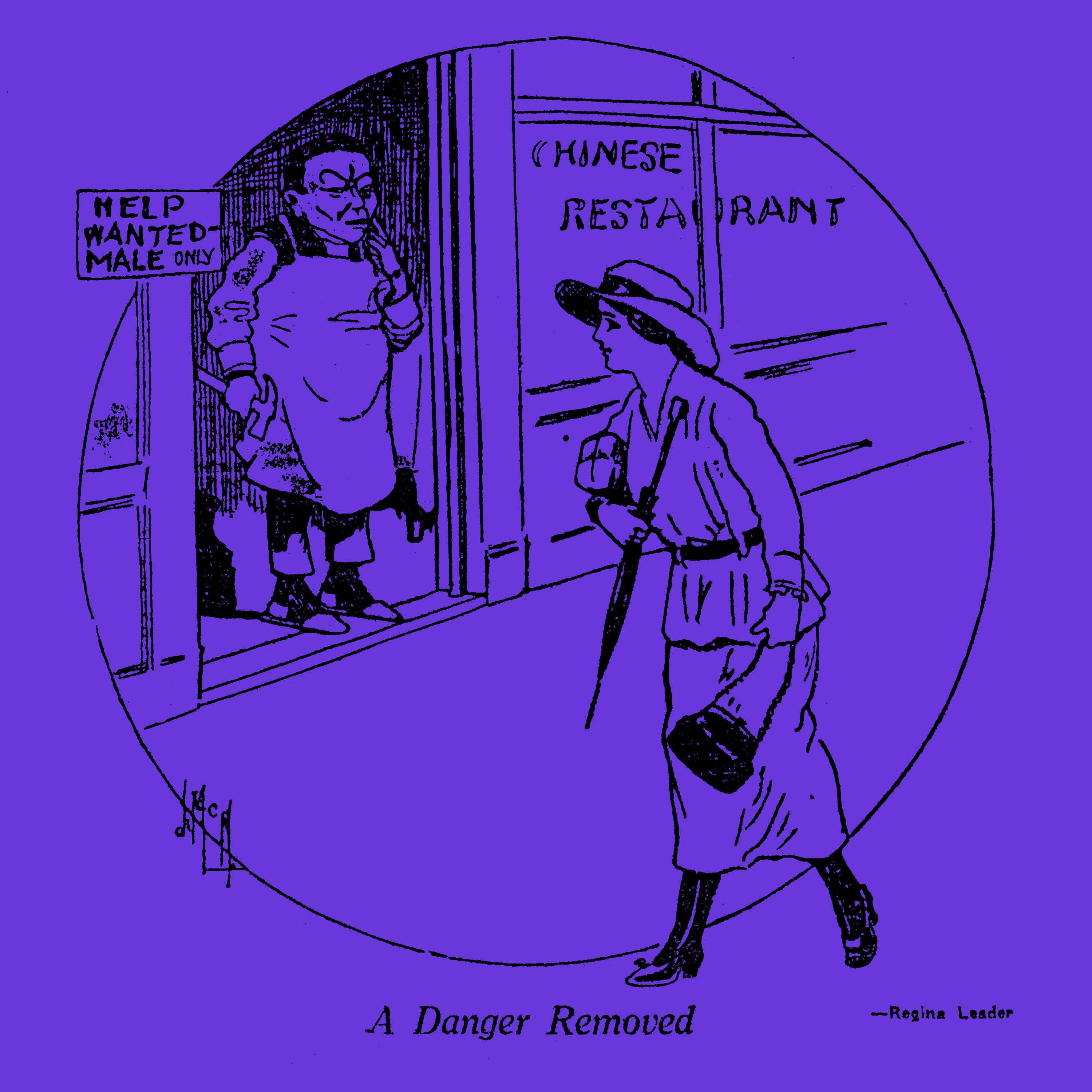

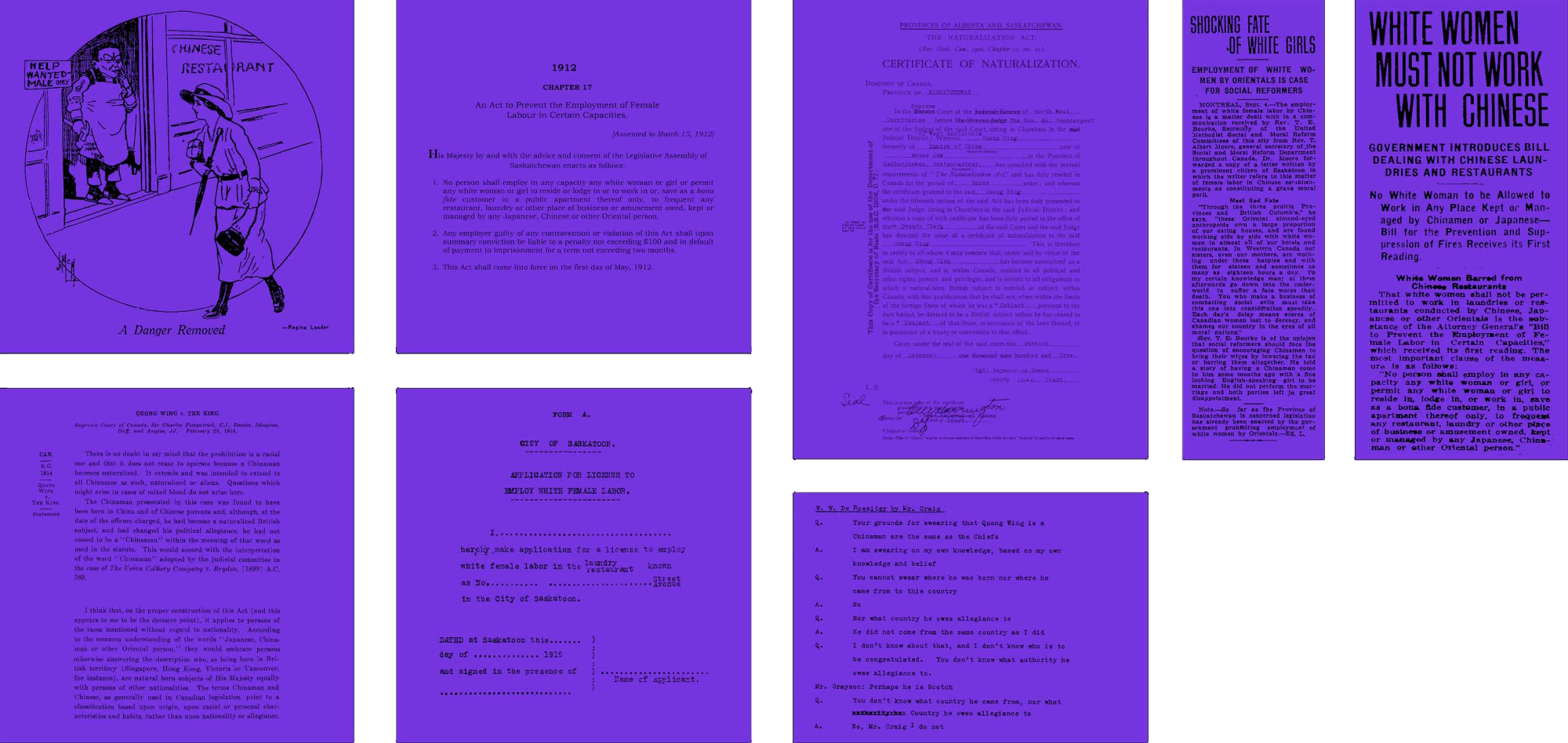

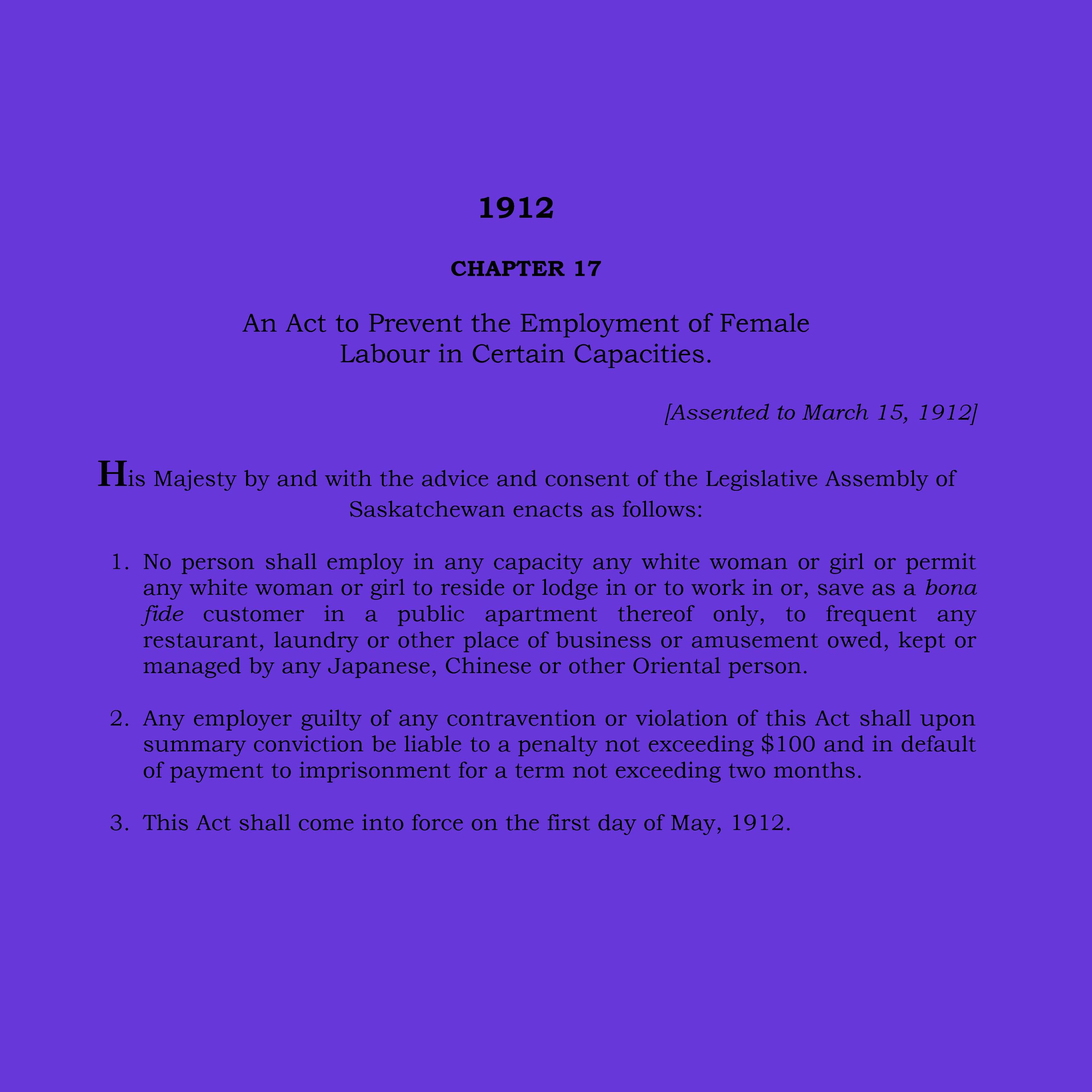

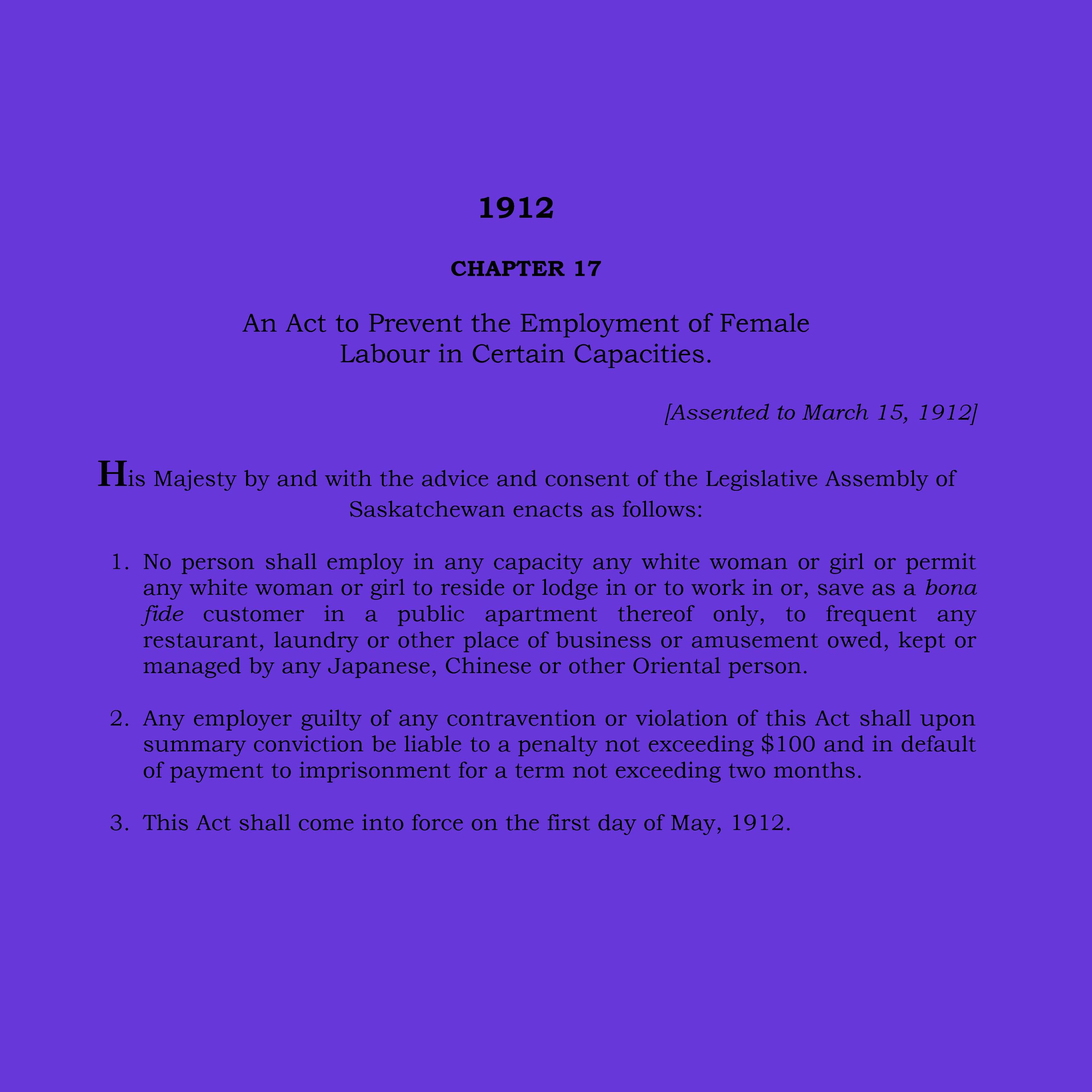

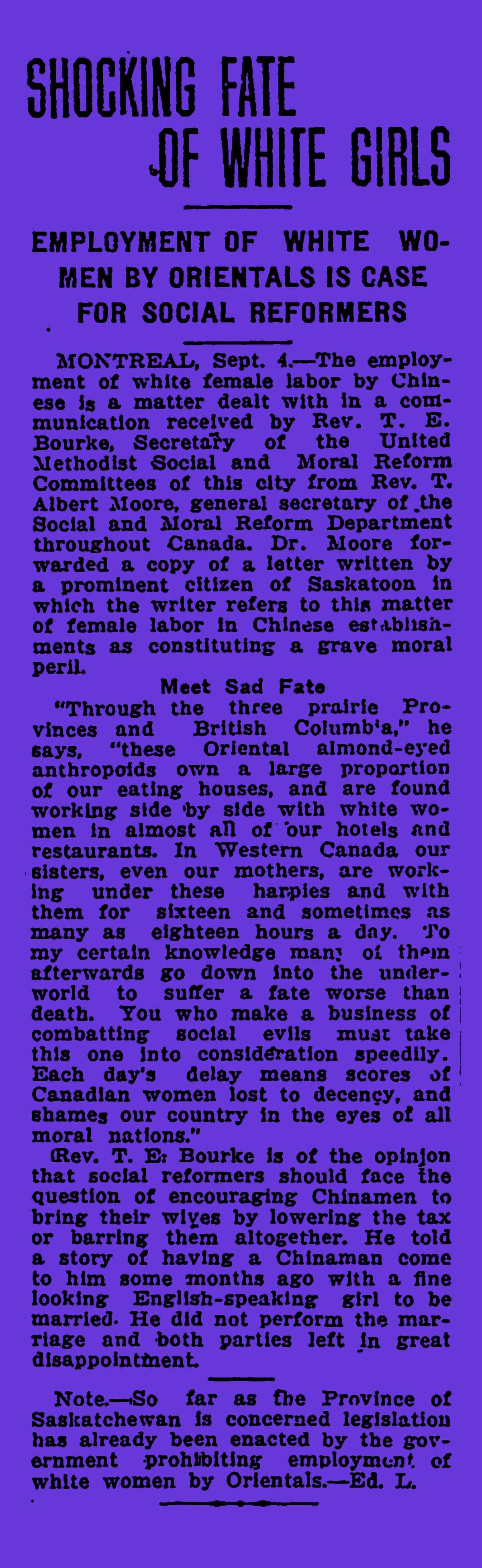

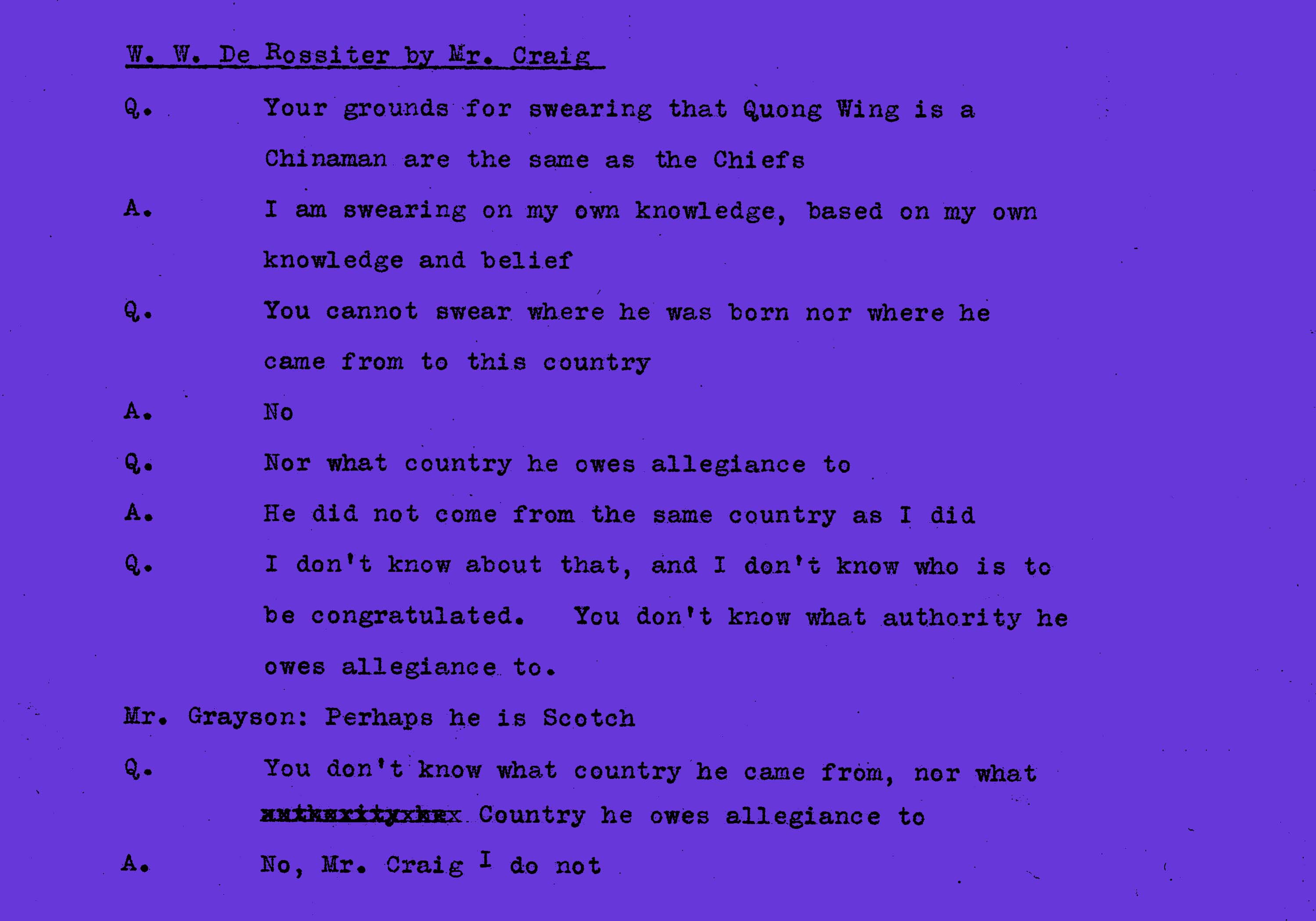

In 1912, Quong Wing ran the CER Restaurant at 1 Main Street in Moose Jaw where he employed two white women, Mabel Hopham and Nellie Lane, to work as waitresses. Enacted in Saskatchewan in 1912, a new statute titled An Act to Prevent the Employment of Female Labour In Certain Capacities made it a criminal offence for Chinese men to employ white women. It started that “no person shall employ in any capacity any white woman in businesses owned, kept or managed by any Chinaman”. Wing was charged and convicted under the provincial statute.

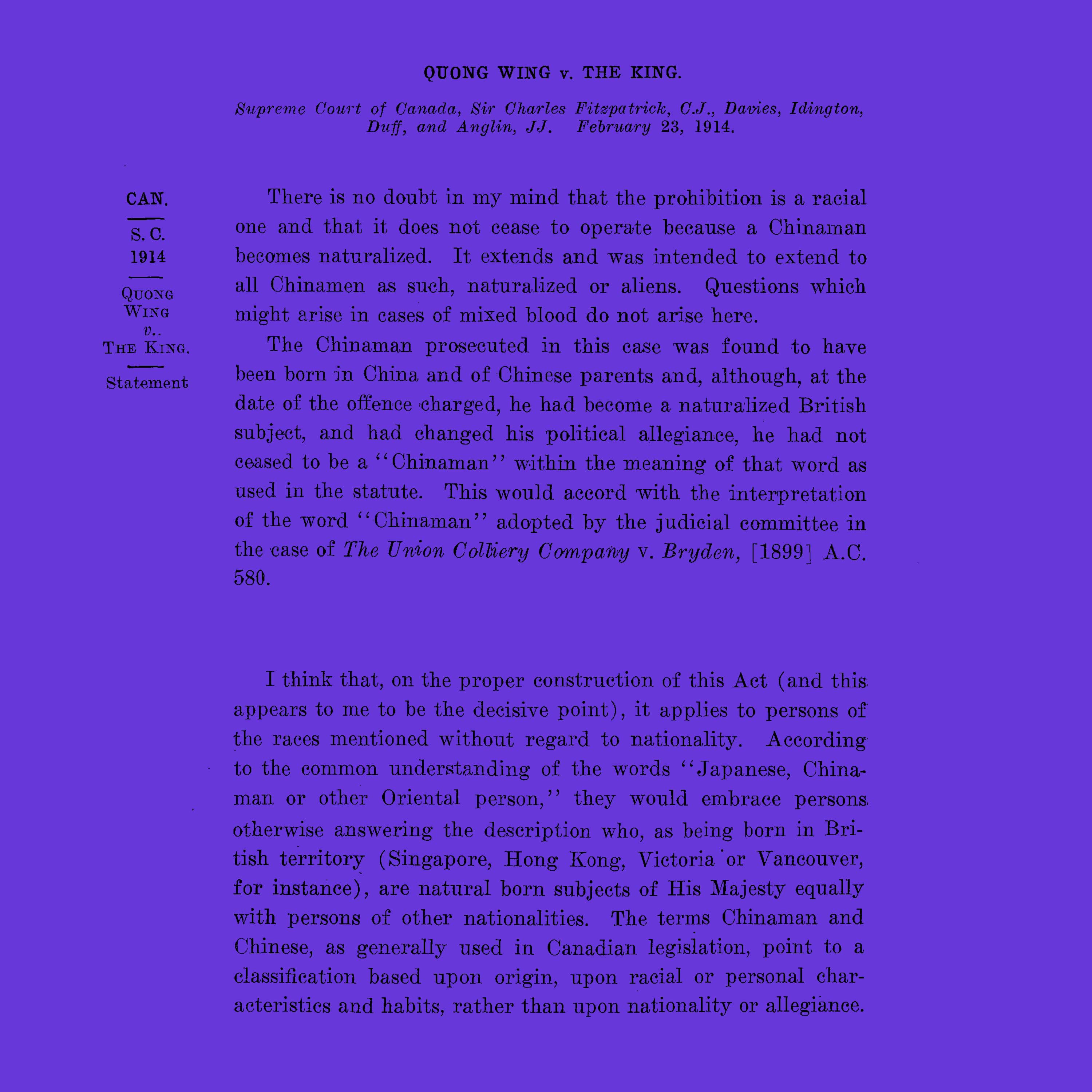

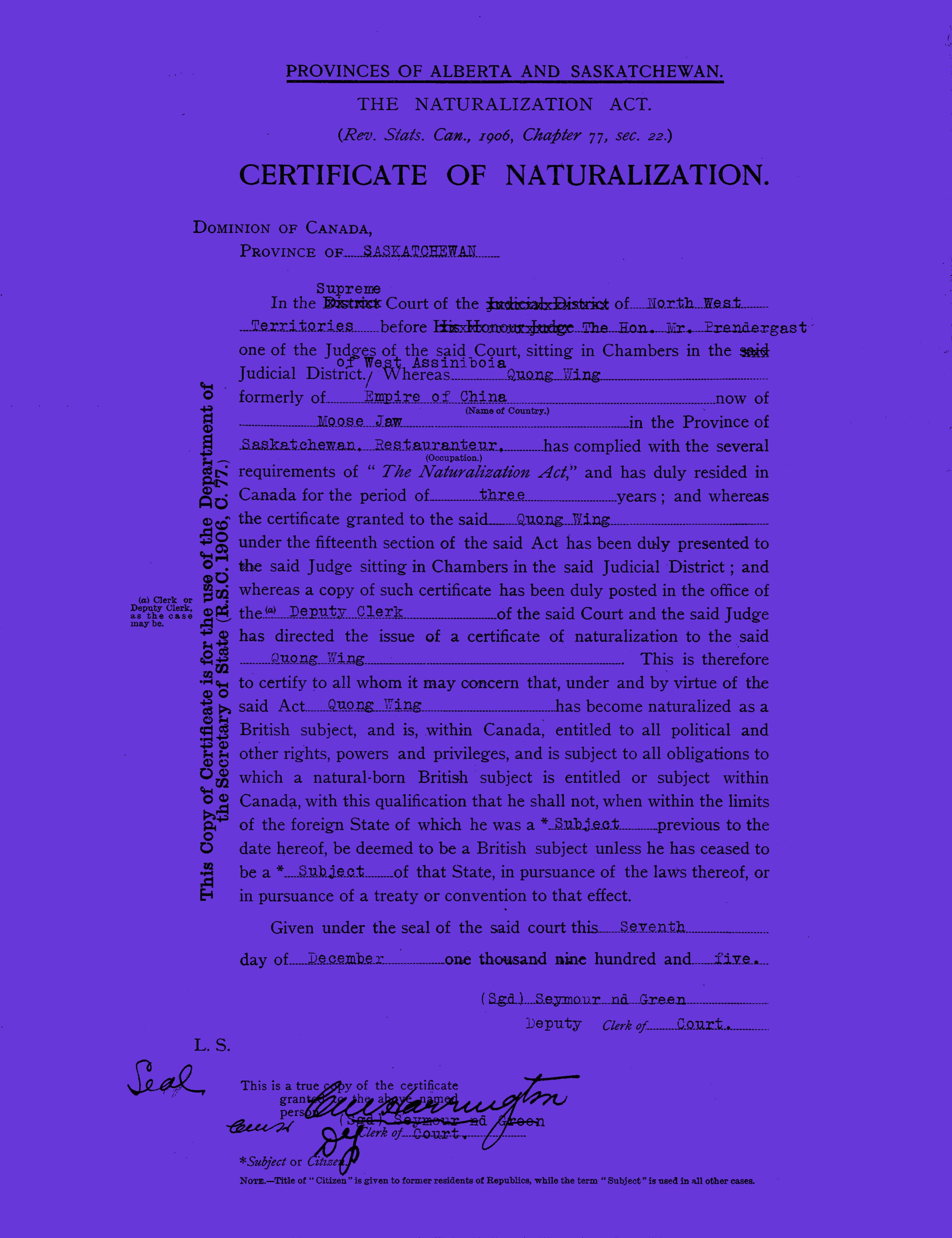

Wing appealed, arguing that the law was outside the jurisdiction of the province and that that the law did not intend to include naturalized citizens. Wing was born in China to Chinese parents but became a naturalized Citizen under the British crown.

During the trial, witnesses were brought forth to testify on whether or not Quong Wing was a Chinaman. His birthplace, the birthplace of his parents, his language and the people in his company were all called into question, resulting in a display of the Crown’s inability to define what constitutes racial status.

The Supreme Court of Canada held in a four to one decision that the law was valid, with the court determining that the Saskatchewan legislature was acting within its rights. Rather than interpreting the Act as excluding Chinese from Canada, the court found that the province was legislating working conditions for white women and girls, which was within its provincial power. The Court interpreted the word “Chinaman” as including all those born in China regardless of subsequent nationality. Judge Louis Henry Davies from the Supreme Court of Canada stated that although Quong Wing “had become a naturalized British Subject and had changed his political allegiance, he had not ceased to be a “Chinaman” within the meaning of that word used in the statue.” The provinces of Manitoba, Ontario, and British Columbia adopted similar or identical statues over the next seven years. The statue would not be repealed until 1969.

A Danger Removed Saskatoon Daily Star July 17, 1913 Accessed from Newspapers.com

An Act to Prevent the Employment of Female Labour March 15, 1912 Accessed from Tunnelsofmoosejaw.com

Quong-Wing v. The King Can lii 608, Pages 128 and 138 February 23, 1914 Accessed from the Canadian Legal Information Institute

Bylaws - Female Labour in Restaurants and Laundries June 10, 1919 City of Saskatoon Archives. Call number D500.VI.230.

Quong Wing, Certificate of Naturalization December 7, 1905 Provincial Archives of Saskatchewan. Call number R-1267.474.

White Women Will Not Work with Chinese The Morning Leader February 27, 1912 Accessed from Newspapers.com

Shocking Fate of White Girls The Morning Leader September 5, 1912 Accessed from Newspapers.com

Evidence for the Prosecution: W.W. De Rossiter Cross-examined by Mr. Craig, Page 6 excerpt July 2 , 1912 Provincial Archives of Saskatchewan. Call number R-1267.474.

SHELLIE ZHANG

Believe it or Not, 2020-2021

THE PLACE TO BE

The Exchange

Café

in Moose Jaw

Witness Number 1 (The Exchange Café in Moose

Jaw)(green),

2020-2021, Archival Inkjet Print, 18x24”

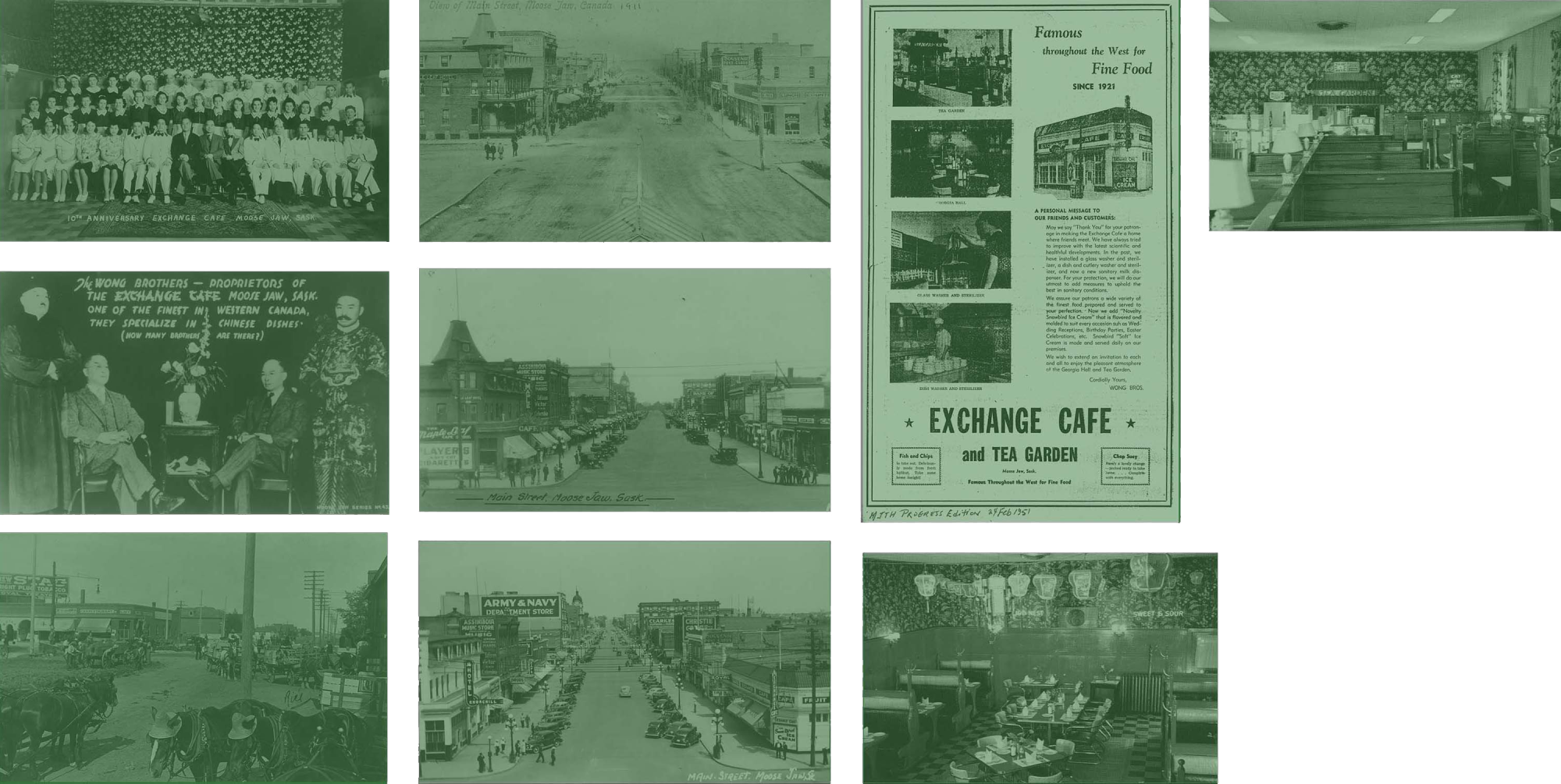

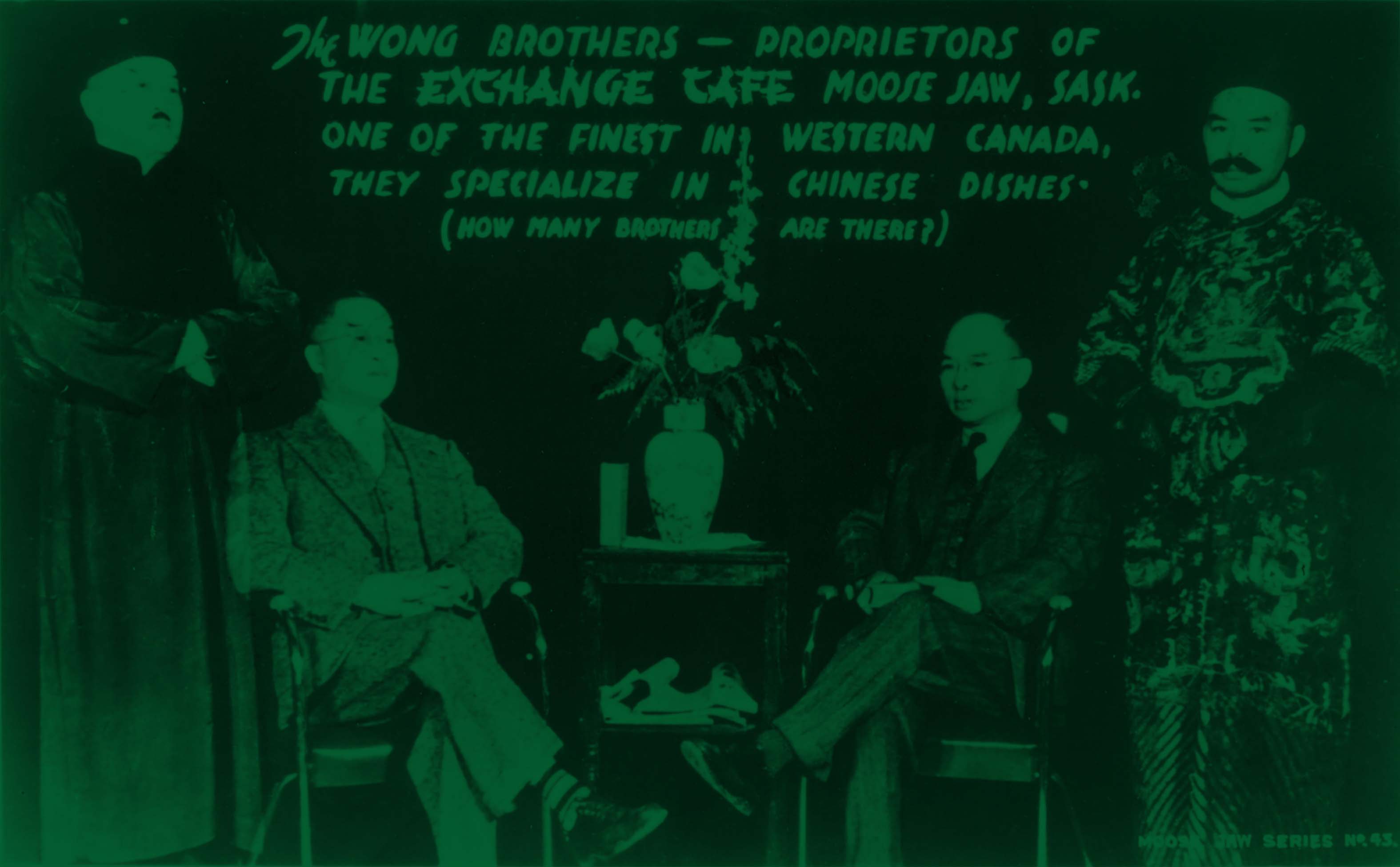

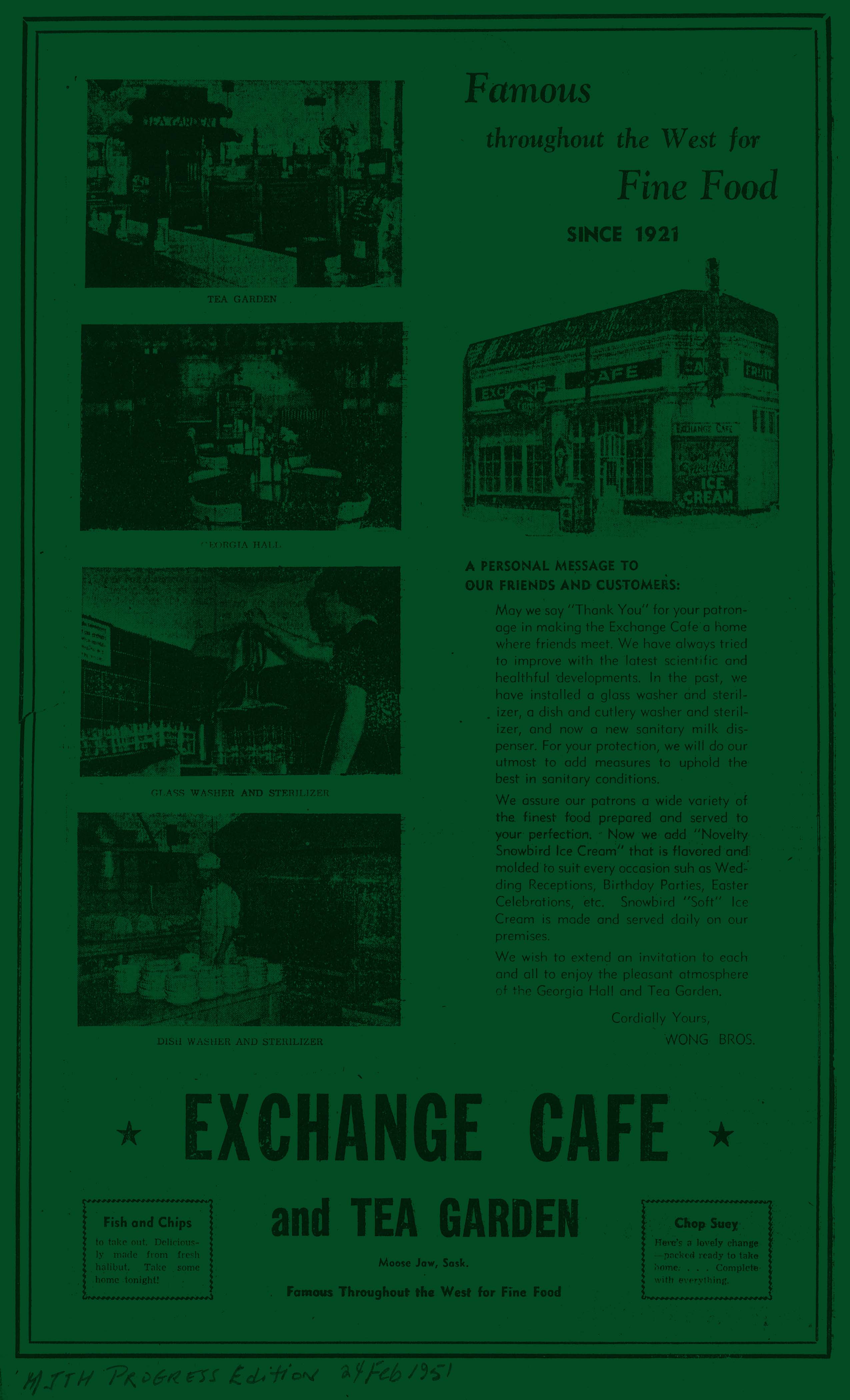

Moose Jaw city directories show that the CER Restaurant eventually became the Exchange Café in 1933 under the proprietorship of brothers George and Charlie Wong. During the Great Depression, many customers would arrive at the doorsteps of the Café looking to barter goods or services for food, earning the restaurant its name. The Café served both Canadian and Chinese cuisine and employed a large team of white waitresses, white and Chinese chefs, and several members of the Wong family. Despite the economy’s desolate times during the Depression and the hostile climate towards Chinese-Canadians, a combination of strategic public relations and the brothers’ charismatic personalities allowed the café to flourish into a neighbourhood favorite.

The Wong brothers integrated a personal touch into their outreach efforts. George and Charlie were always at the front of the restaurant. When they heard word of a new baby born in town, they would send a card to the family to congratulate them, while also gently reminding the parents that the café’s services could alleviate some of the pressures of raising a family. Christmas dinners were booked a year in advance. Due to its convenient location next to the train station, visitors from Regina would visit just to dine at the café. Over time, the Exchange Café would be promoted through its then top of the line appliances, service and expansions. Ads in local newspapers would boast about the café’s large fridge, component chefs, growing capacity, and Snowbird ice cream. The restaurant even had the first dishwasher in Moose Jaw. As the Chinese community grew over time, the café began to stock Chinese goods and groceries. When the Exchange Café celebrated its seven-year anniversary, many local businesses, some who worked with the restaurant, took out ads to congratulate them.

Charlie died in 1968 and George in 1982. When Charlie passed away, all the flower shops in Moosejaw were sold out. George is remembered as a generous person who assisted anyone in need, especially many new immigrants to Canada. In 1972, Charlie’s eldest son Key and his wife Ruth converted the Café’s property into the City Centre Motel, which they ran until they retired in the 1990’s. In the 21st century, the city capitalized on the notoriety surrounding unproven speculation that Al Capone used the tunnel network near the railway to smuggle alcohol during prohibition. Not long after, 1 Main Street became Capone’s Hideaway Motel, across the street from the infamous Tunnels of Moose Jaw attraction.

Several Teams of Horses at the C.P.R. Freight Shed: Left: C.E.R Restaurant 1910-1913 Moose Jaw Public Library, Archives Department. Call number 2004-57 mjpl:34672

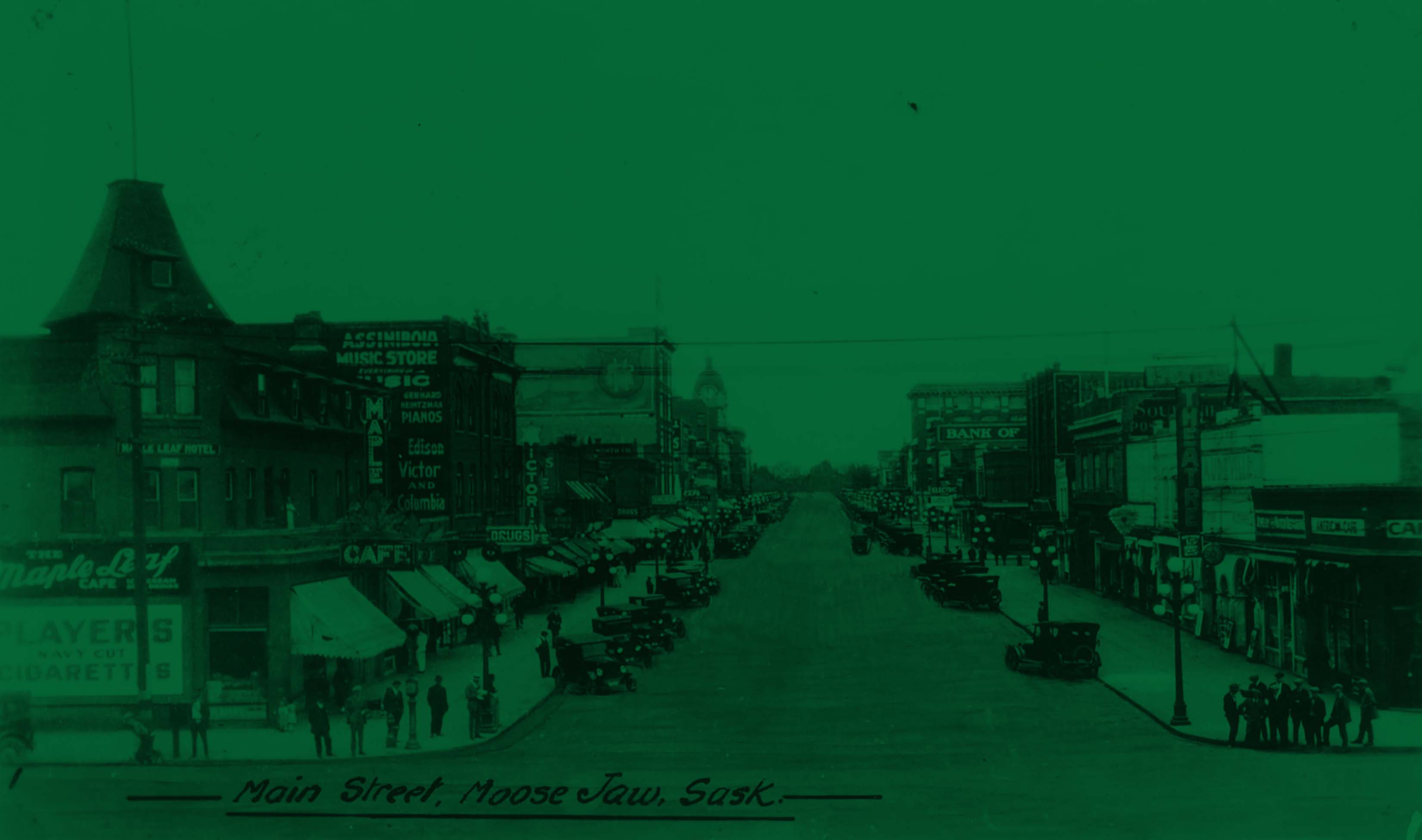

Main Street of Moose Jaw Right: C.E.R Restaurant 1911 Accessed from Flickr. User Moosejaw.

Main Street of Moose Jaw Ca. 1934 Accessed from Flickr. User Moosejaw.

Main Street of Moose Jaw Right: Exchange Café Date After 1940 Accessed from Flickr. User Moosejaw.

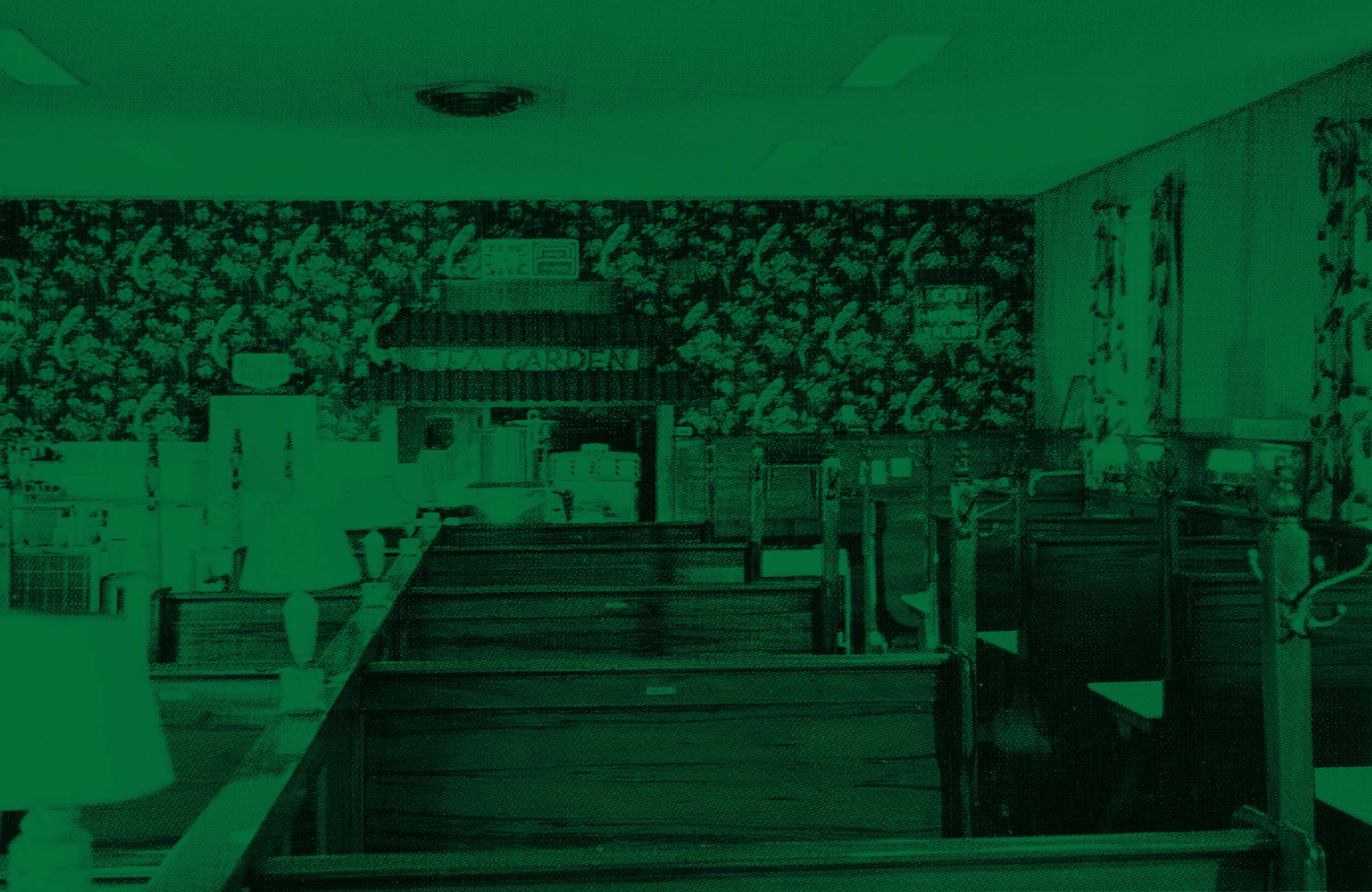

Interior of Exchange Café Date Unknown Postcard Moosejaw Archives and Library. Call number Photo 73-15

Interior of Exchange Café Date Unknown Postcard Moosejaw Archives and Library. Call number Photo 73-15

The Wong Brothers Date Unknown Accessed from Flickr. User Moosejaw

10th Anniversary Exchange Café Date Unknown Accessed from Flickr. User Moosejaw.

Exchange Café Advertisement Moose Jaw Times Herald - Progress Edition February 24, 1951 Moosejaw Archives and Library.

SHELLIE ZHANG

Believe it or Not, 2020-2021

MAKE WAY FOR

THE NEW

AT

THE EXPENSE

OF

THE OLD

Chinatowns

Coming and Going

Exhibit C (Chinatowns Coming and Going)(yellow),

2020-2021, Archival Inkjet Print, 18x24”

During the late 1800s and early 1900s, the completion of the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR), the unemployment rate among the Chinese in British Columbia, and the hostility from white Canadians led to groups of Chinese settlers leaving the province. New railway towns became popular locations for resettlement and the Chinese community moved eastward to seek new lives in the Prairies.

In the early 1900s, Chinese settlers established a small Chinatown in Saskatoon with a few businesses including Chinese laundries, grocery stores, and restaurants. In the early 1920s, this neighbourhood was concentrated in old dwellings and business spaces on Nineteenth Street, at the end of Second Avenue. Chinese establishments were also geographically scattered areas of the city outside of this hub. Suspicion and prejudice toward this small community was not uncommon and the city’s initial Chinatown did not survive long. In 1929, the first Chinatown was cleared to provide a central site for the Technical Collegiate, a new Legion building, and later an Arena. This destruction fell at the end of the City Beautification era of urban development, where Chinatowns were commonly seen as eyesores and sites of deviance. The premeditated plan for Chinatown’s destruction can be observed in cities across North America. Chinatowns in Chicago, Los Angeles, Seattle and Washington D.C were moved to a different part of the downtown core in the early twentieth century. In Toronto and Detroit, Chinatown was displaced to another downtown location postwar. Cities such as Detroit, Pittsburgh and St. Louis no longer have Chinatowns.

By the end of World War II, the Chinese Immigration Act was repealed and families were reunited, centered around 20th Street. After the mid-1960s, a few Chinese restaurants and stores were set up on 20th Street West between Avenue B and Avenue D South. By November 1986, Saskatoon’s new Chinatown consisted of about twenty Chinese business concerns widely spaced along 20th street west between Ave A and Ave H and on Ave C. 424 20th Street which is the current location of AKA Artist-Run and Paved Arts once housed a Chinese restaurant named Toon’s Kitchen. The birth of a new Chinatown in Saskatoon is mainly a result of the increasing demand for Chinese merchandise and services from a rapidly growing community. 20th Street is now largely home to older Chinese businesses and new businesses that have opened since the River Landing development. With the suburbanization of Chinese Canadians, gentrification of Chinatowns and the impact of COVID-19 on social biases, many question whether downtown Chinatowns will survive.

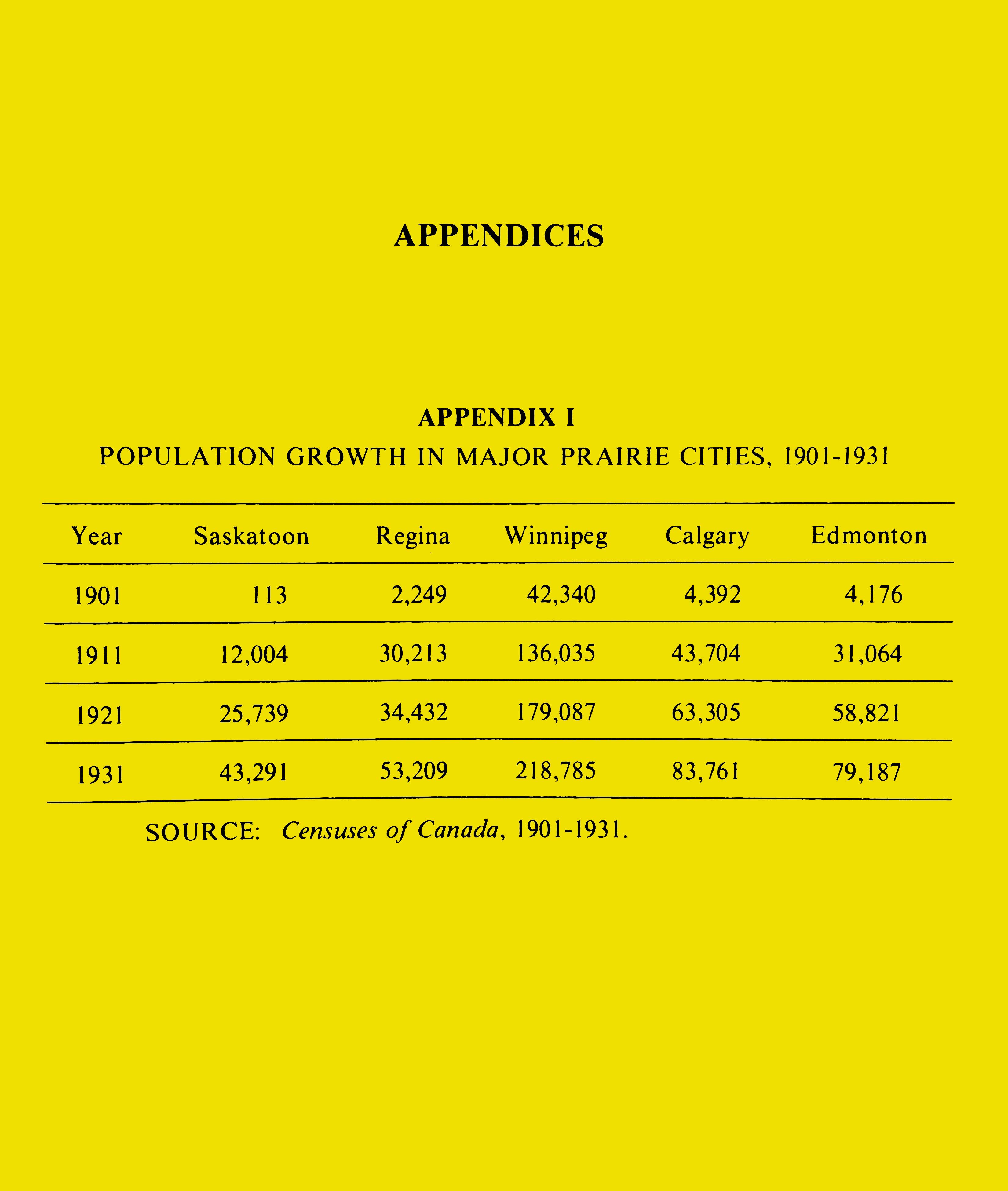

Appendix I: Population Growth in Major Prarie Cities 1901-1931 In Saskatoon: The First Half Century by Don Kerr and Stan Hanson, Page 315 Published 1982

Travellers’ Day parade. July 23, 1926 Saskatoon Public Library. Call number. LH1147

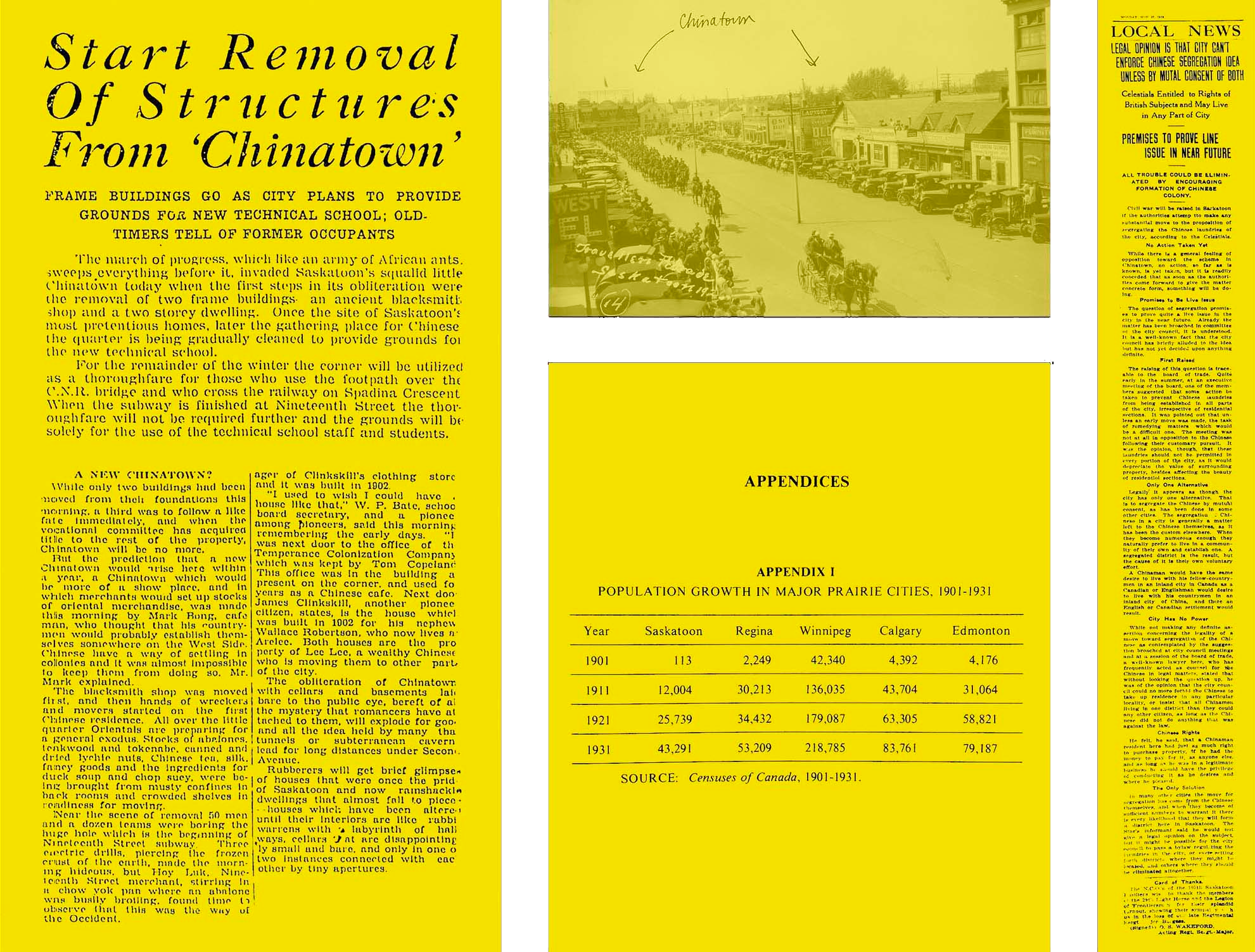

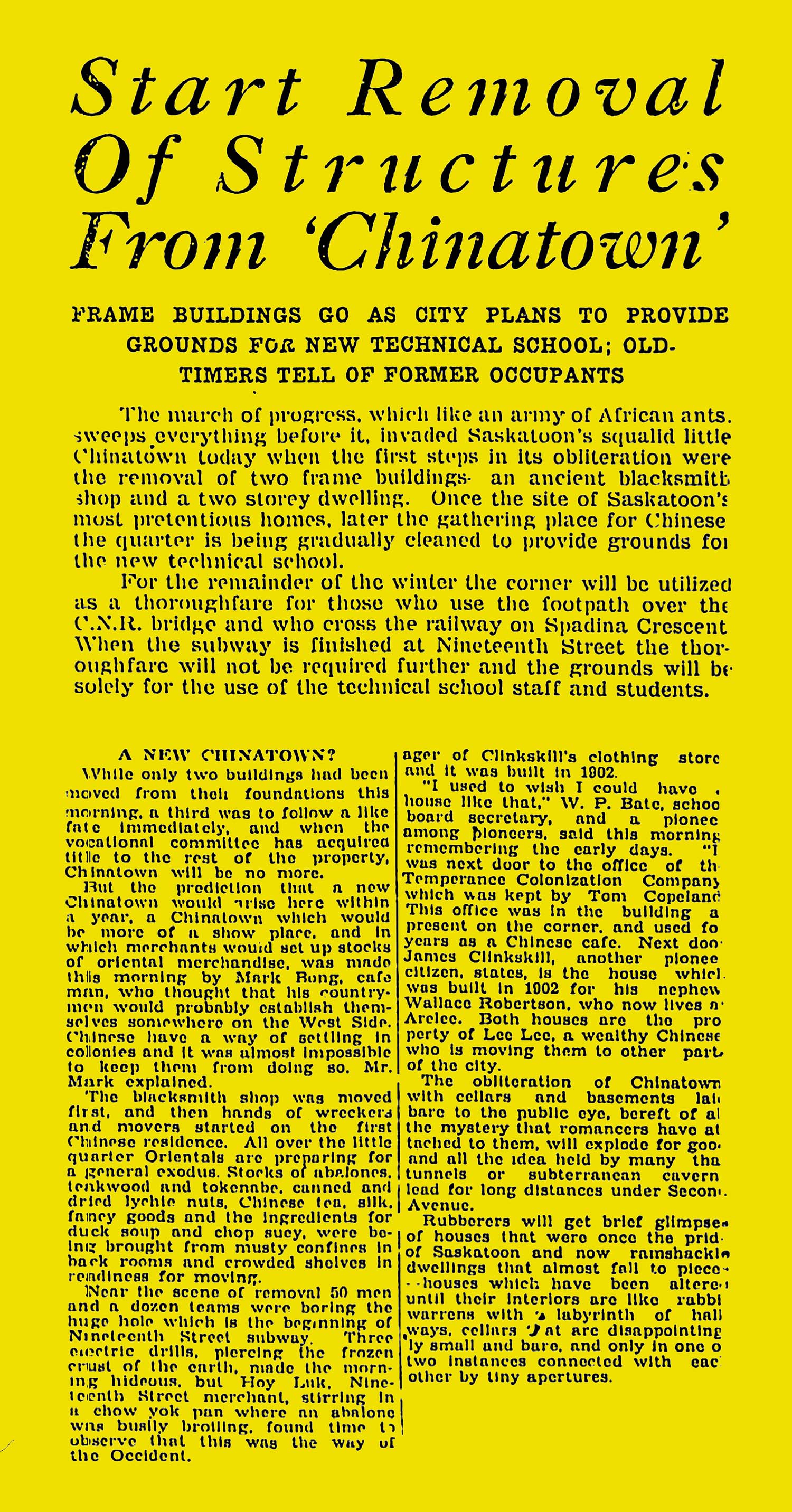

Start Removal of Structures from ‘Chinatown’ Saskatoon Star-Phoenix December 17, 1930 Accessed from Newspapers.com

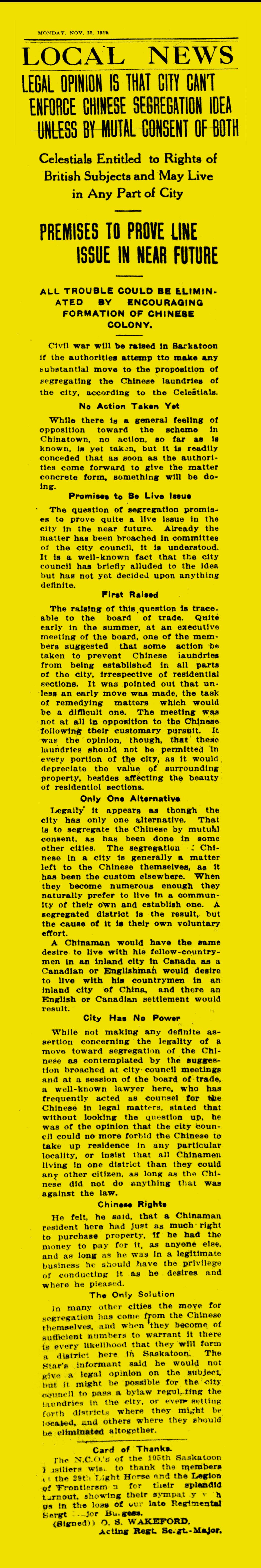

Legal Opinion is that City Can’t Enforce Chinese Segregation Idea Unless by Mutual Consent of Both Saskatoon Daily Star November 25, 1912 Accessed from Newspapers.com

SHELLIE ZHANG

Believe it or Not, 2020-2021

A SIGHT TO BEHOLD

The Chinatown

Gate that

Could

Have Been

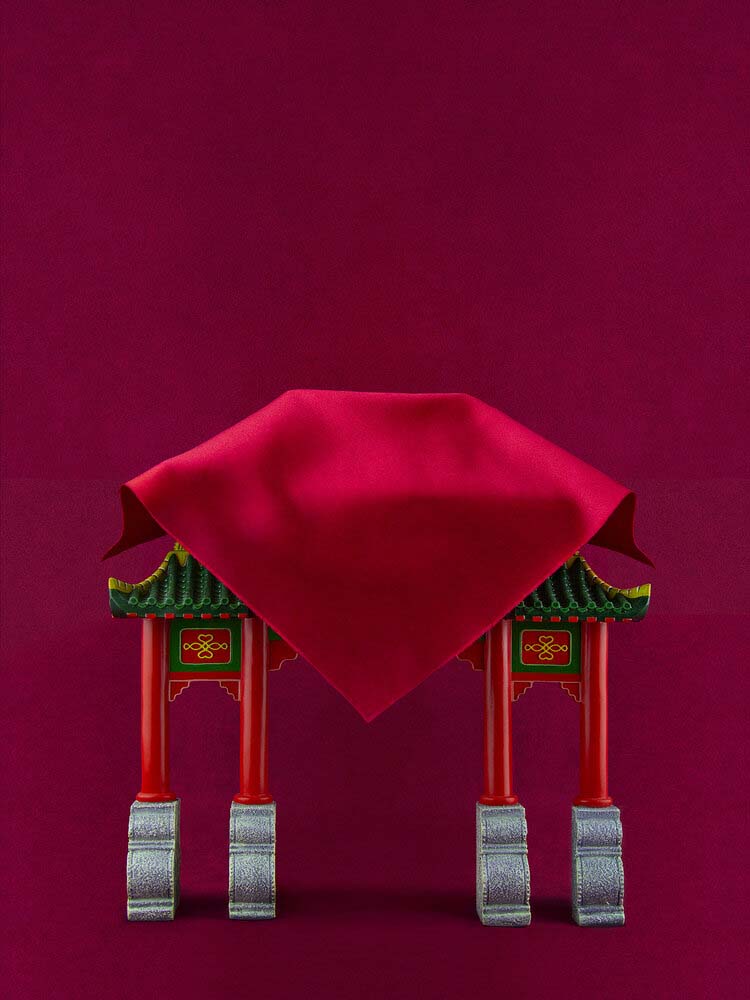

Exhibit C (Chinatowns Coming and Going)(yellow),

2020-2021, Archival Inkjet Print, 18x24”

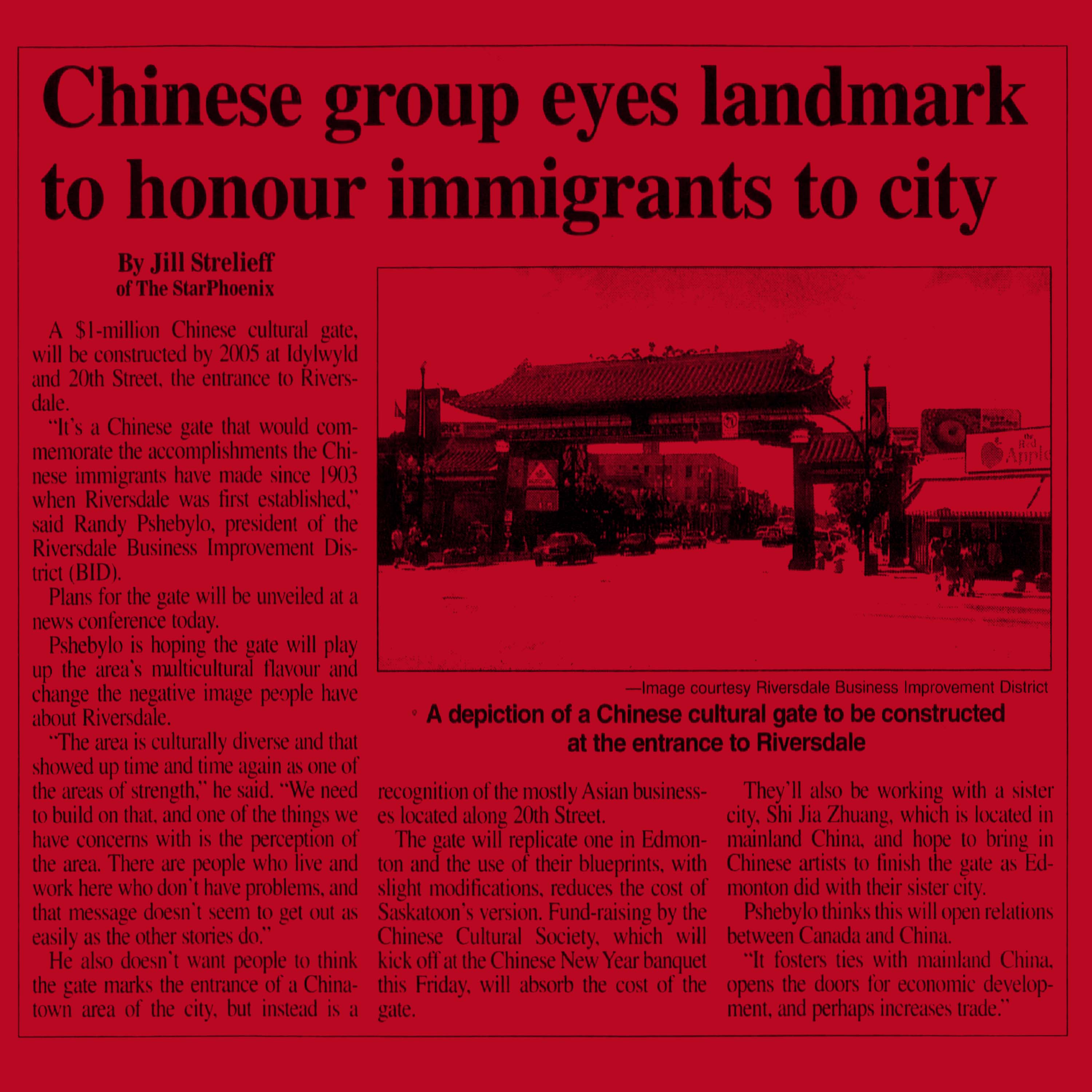

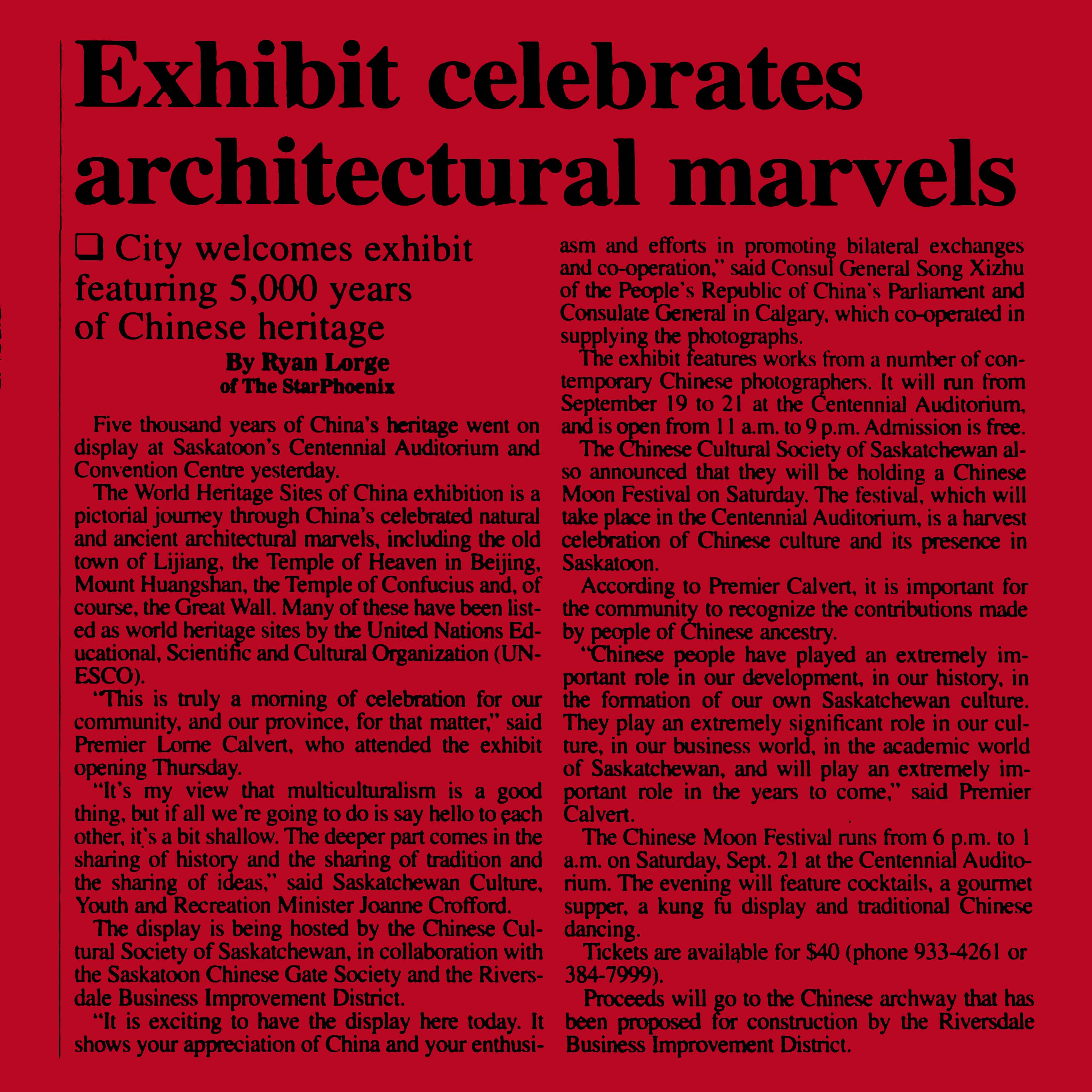

In 2002, a proposed $1-million Chinese cultural gate was to be completed by 2005 at the entrance to Riversdale at Idylwyld Drive and 20th Street East. This gate was intended to commemorate the accomplishments of Chinese settlers since 1903 when Riversdale was first established. The Riversdale Business Improvement Area had hoped this gate would emphasize the area’s multicultural history and alter the then negative image associated with the neighbourhood. This proposed gate was going to be modeled after an existing one in Edmonton through the use of its blueprints with slight modifications. Edmonton’s gate was presented to the city by their twin city of Harbin. Similarly, Saskatoon was going to consult with its sister Chinese city Shi Jia Zhuang.

In 2008, the City’s local area plan still hoped to erect signage/gates either upon entering Riversdale or have the signage/gates placed along 20th Street in order to reflect the neighbourhood’s First Nations, Ukrainian and Chinese communities. The gate was never completed. There are speculations that fundraising and bureaucracy became a barrier.

In 2015, the Zhongshan Ting Committee donated a new ting to Victoria Park in Riversdale to commemorate the first Chinese immigrants and their contributions to early Saskatoon—the intended goal for the gate.

In November 2017, Edmonton’s Harbin Gate was removed for the Valley Line LRT construction. The city had agreed to find a new location for the gate but plans stalled post-takedown. There are also structural issues in putting the gate back together. For two years, the gate sat in storage until mounting pressure from community organizers made the city consider alternative solutions, such as mounting a replica in a new location. The proposed new gate would commemorate where Edmonton’s original Chinatown settlement once was at 101A Avenue and 97th Street. A large federal office building named Canada Place is currently located at this address. Its completion in the late 1980s resulted in numerous Chinese businesses being pushed out.

Chinese Group Eyes Landmark to Honour Immigrants to City Saskatoon Star-Phoenix February 5, 2002 Accessed from Newspapers.com

Exhibit Celebrates Architectural Marvels Saskatoon Star-Phoenix September 20, 2002 Accessed from Newspapers.com

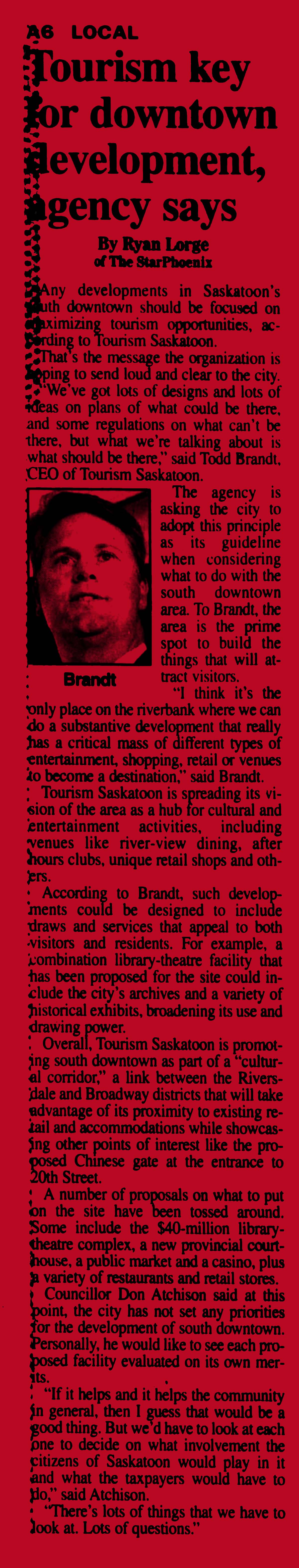

Tourism Key for Downtown Development, Agency Says Saskatoon Star-Phoenix October 5, 2002 Accessed from Newspapers.com

SHELLIE ZHANG

Believe it or Not, 2020-2021

STRENGTH

IN NUMBERS

Wing Lee

Laundry

and the

Saskatoon

Chinese

Laundry

Petition

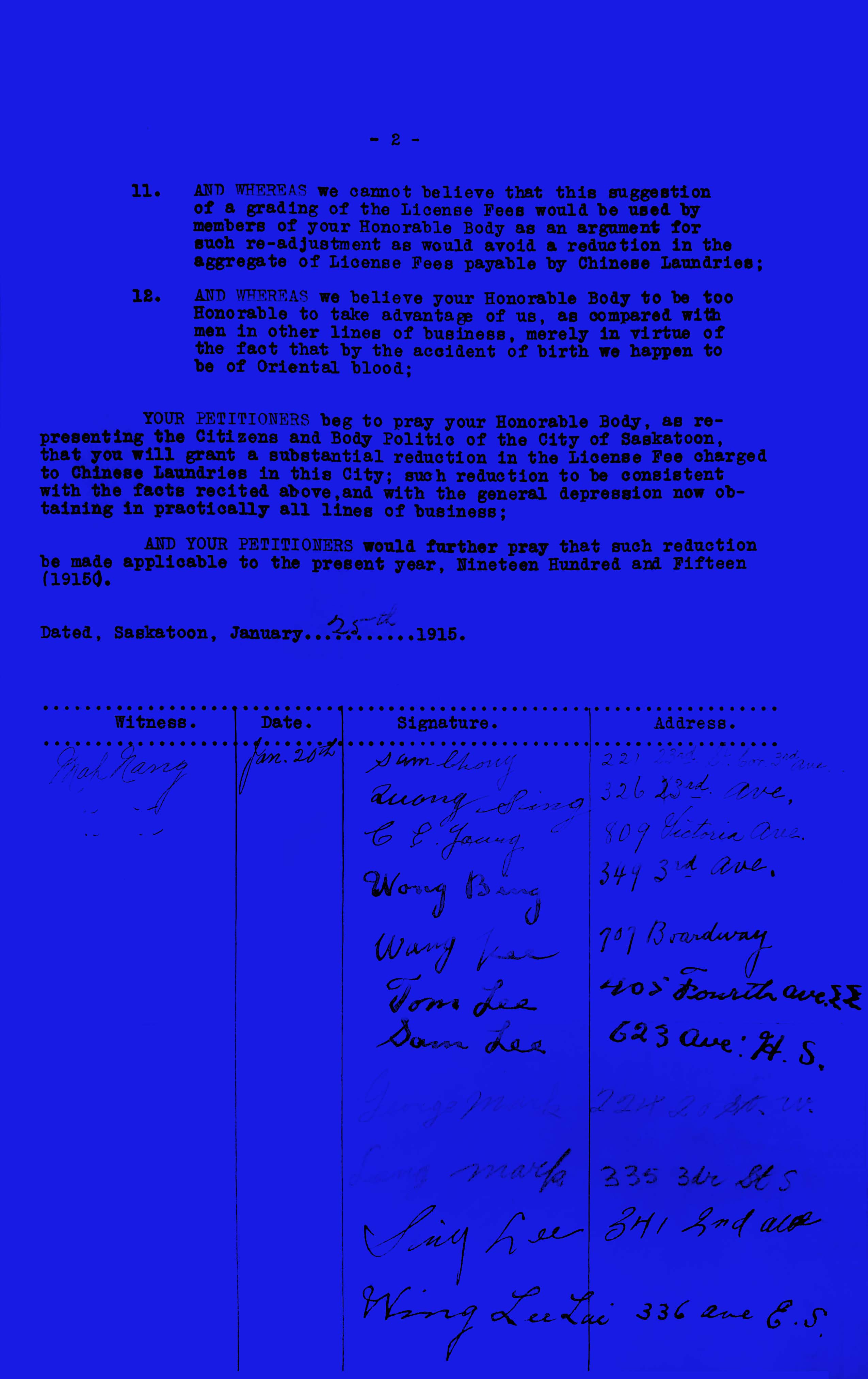

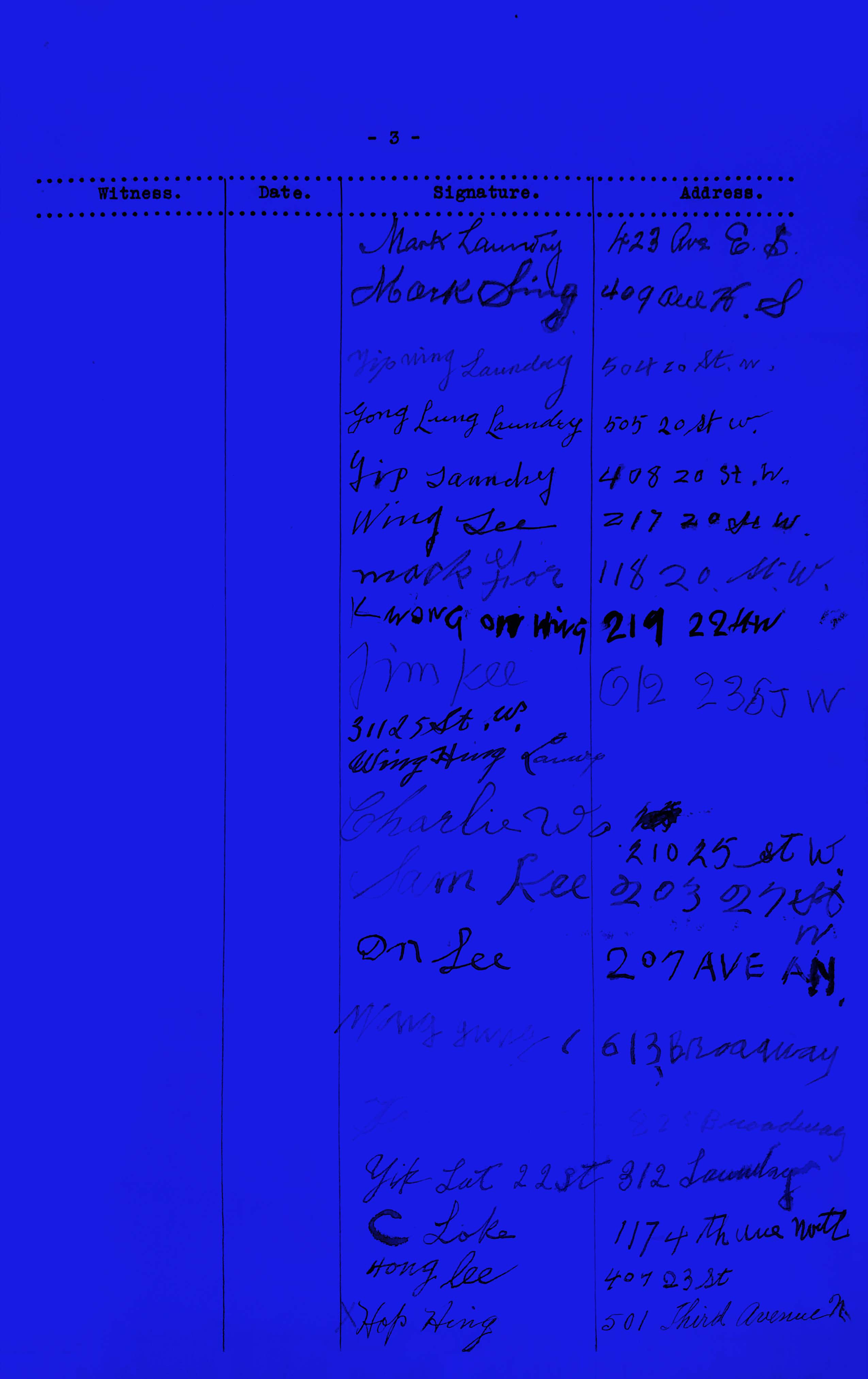

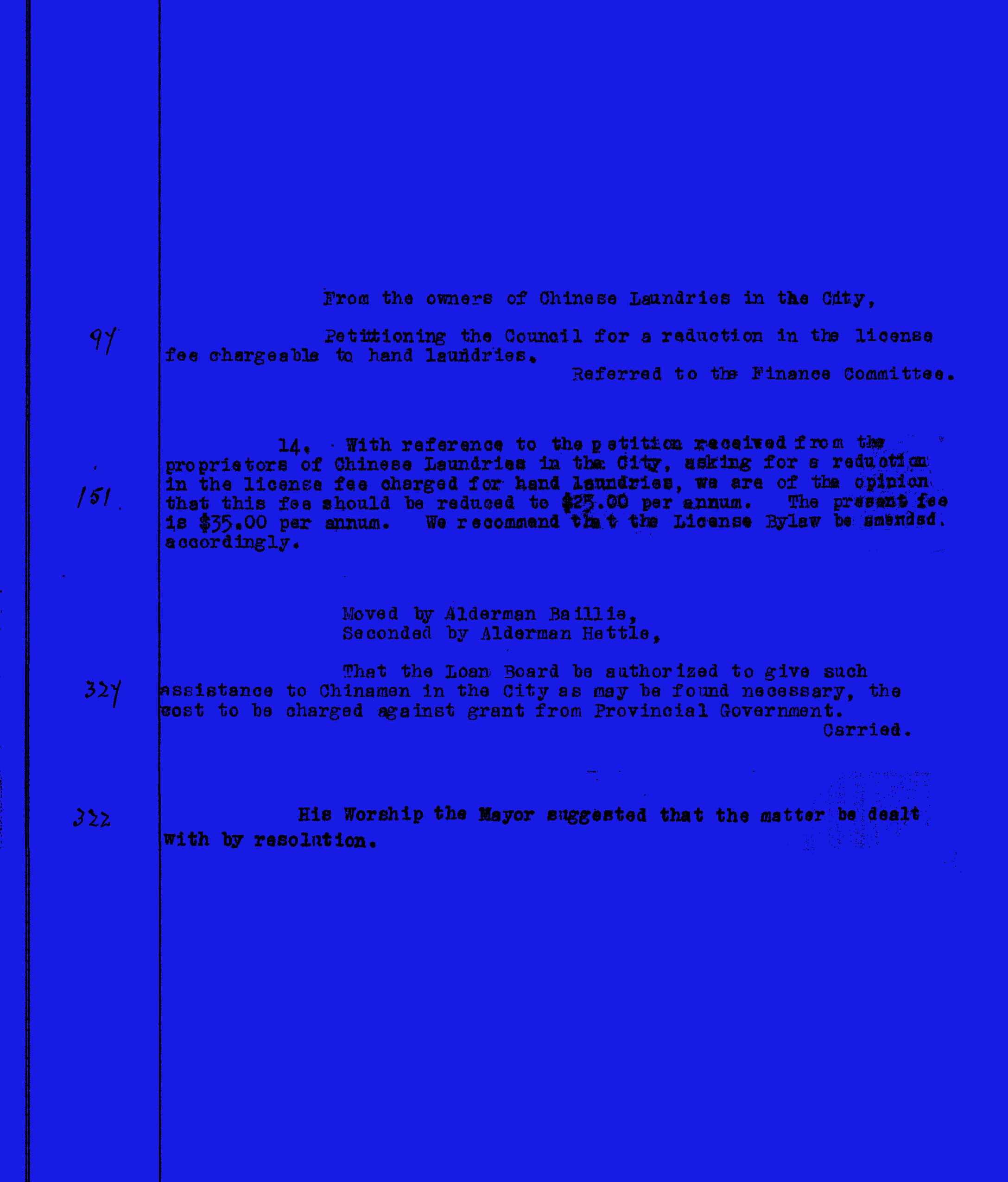

Exhibit B (Wing Lee Laundry and the Saskatoon Chinese

Laundry

Petition)(blue), 2020-2021, Archival Inkjet Print, 18x24”

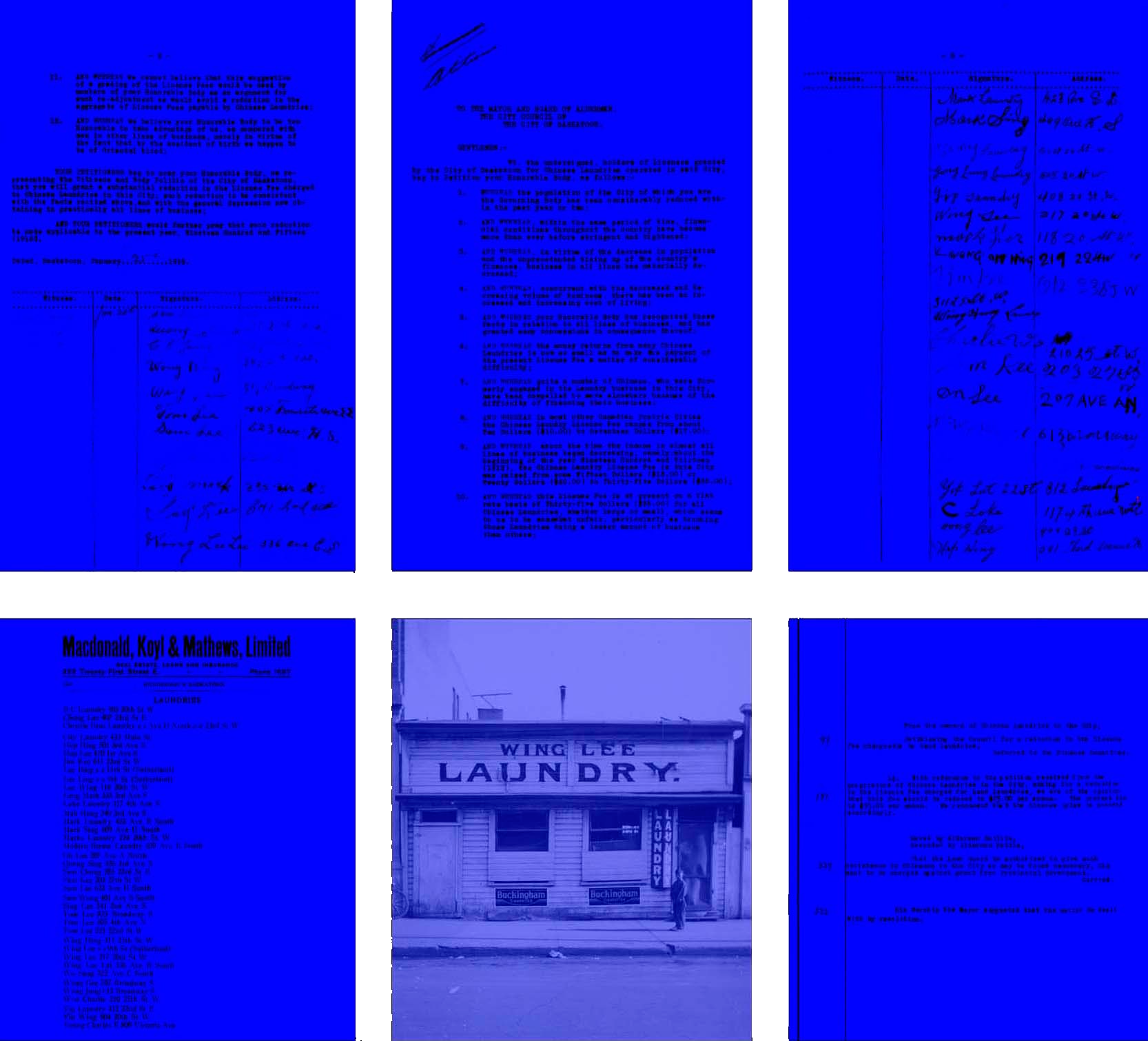

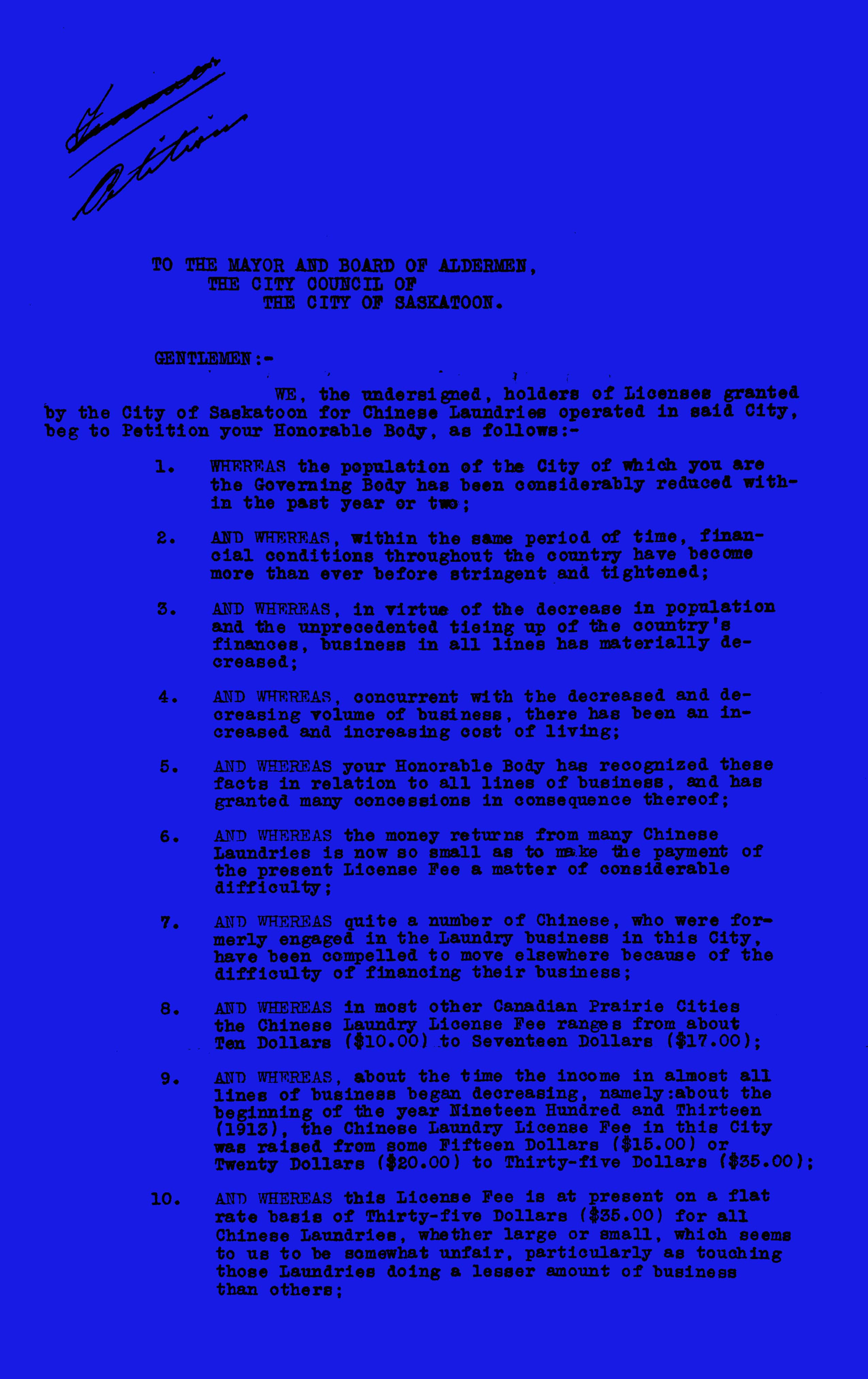

On January 25, 1915, a petition signed by 30 Chinese laundries operating in Saskatoon was sent to the Mayor and City Council regarding a recent licencing fee spike for Chinese laundries from $15 to $35 ($328 to $765 by present day standards). At this time, other Canadian cities had fees ranging from $10 to $17. The low income of many Chinese laundries meant payment for a licensing fee was a matter of considerable difficulty. Additionally, at the federal level, the Chinese Immigration Act charged individuals with a $500 tax ($10,930 by present day standards). A number of Chinese laundries were compelled to move elsewhere because of the challenges in financing their business. This community coalition of business owners mobilized and boldly stated that the city was taking advantage of those who, “by accident of birth, happen to be of oriental blood”, in comparison with other business owners in the same line of work. The petition resulted in the city lowering the annual licence fee to $25 and a motion ensuring that the Loan Board be authorized to give assistance to Chinese business owners as necessary. However, the effectiveness of these concessions may have not been enough. In 1915, 32 laundries in Saskatoon are distinguishable as Chinese. This number was reduced to 29 by 1916-17.

The proliferation of Chinese laundries was a result of circumstance rather than choice. Similar to cooking, laundry was seen as ‘women’s work’, and unbecoming for the likes of white men. In 1879, the Select Committee on Chinese Labour and Immigration of the House of Commons pointed out that, “wash[ing] clothes, which white men who can get anything else to do will not do- this labour is left to the Chinamen”. The majority of organized labour in Canada was also opposed to Chinese immigrants. Eventually Chinese laundries were seen as taking business away from white-owned laundries. Various anti-laundry acts targeting Chinese laundries were passed in cities such as Hamilton, Lethbridge, Calgary, Vancouver, Kamloops, Winnipeg, Toronto and Ottawa.

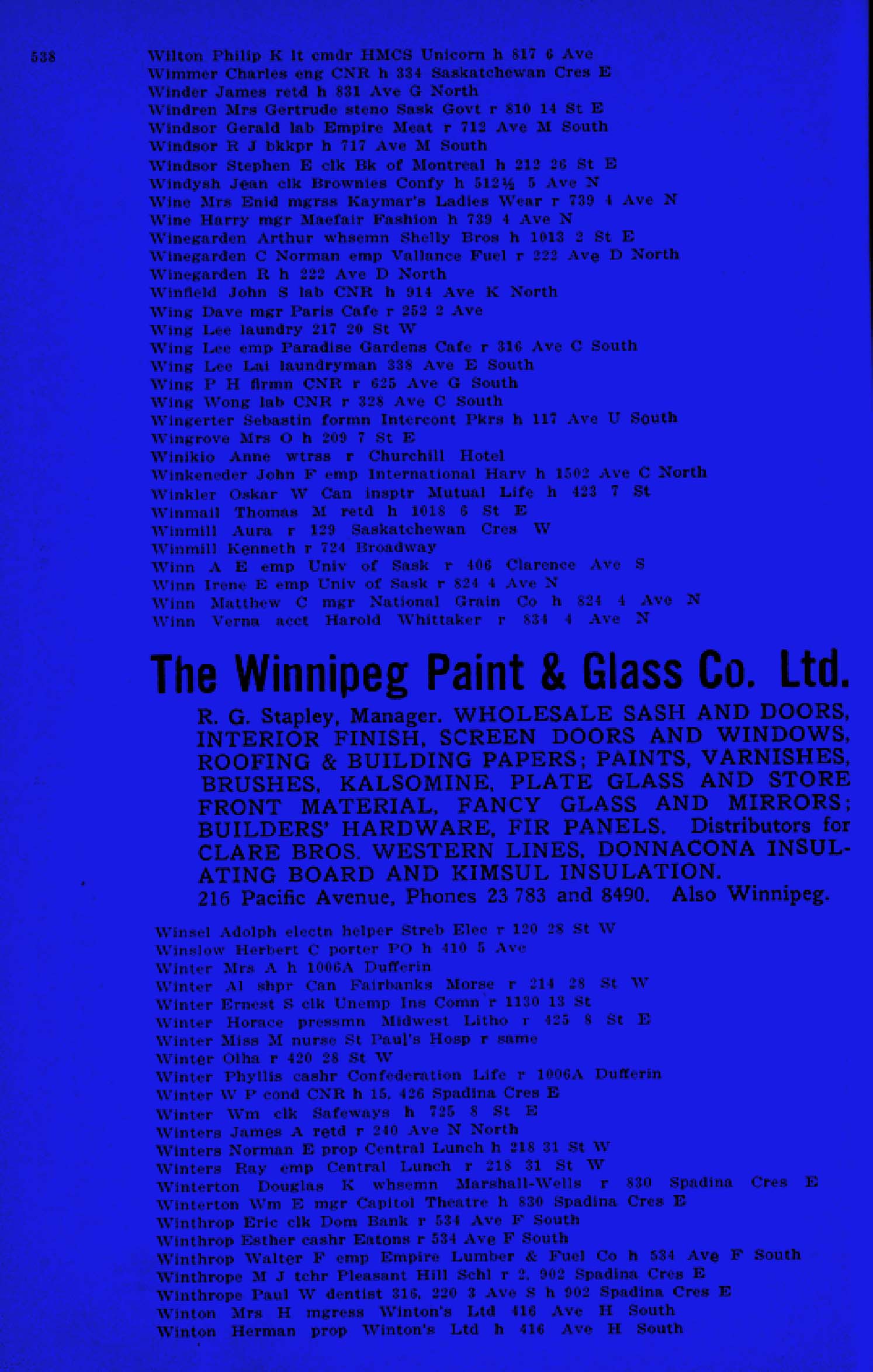

A popular name, in 1915, two Wing Lee laundries are listed in the city directory. This grew to four in 1916 and 1917. A staging of a Wing Lee laundry can be found at the Western Development Museum in Saskatoon, an indoor recreation of a 1910-era “boomtown” with buildings from the era. As of March 2021, no didactic information is given—the only indication that this re-enactment references the history of Chinese laundries can be found in the shop’s sign, which states the business’s name in chop suey font. The laundry is on the list of exhibits to be revisited, refurbished and interpreted in the coming years by the Museum.

Henderson’s Directories – Laundries 1915 City of Saskatoon Archives.

Henderson’s Directories – Laundries 1915 City of Saskatoon Archives.

Letter to the Mayor and Board of Aldermen, The City of Saskatoon January 25, 1915 City of Saskatoon Archives. Call number D50.VI.514.

Letter to the Mayor and Board of Aldermen, The City of Saskatoon January 25, 1915 City of Saskatoon Archives. Call number D50.VI.514.

Letter to the Mayor and Board of Aldermen, The City of Saskatoon January 25, 1915 City of Saskatoon Archives. Call number D50.VI.514.

Facade of the Wing Lee Laundry at 217 20th Street West. Ca. 1948 Saskatoon Public Library. Call number. ph-2017-126-1.

City Council Index Cards, Page 3528 January 15, 1915 City of Saskatoon Archives.

SHELLIE ZHANG

Believe it or Not, 2020-2021

SYMBOL OF

WORLD FAMOUS

GENUINE

CHINESE

FOOD

The Golden Era of

the

Golden Dragon

Restaurant

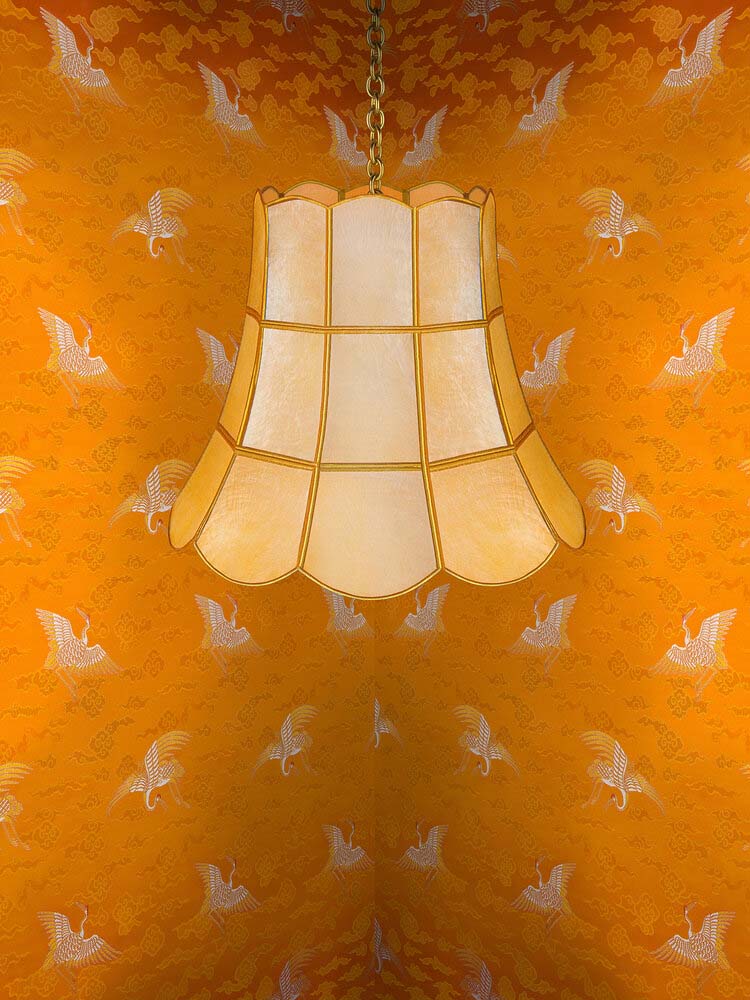

Exhibit C (Chinatowns Coming and Going)(yellow),

2020-2021, Archival Inkjet Print, 18x24”

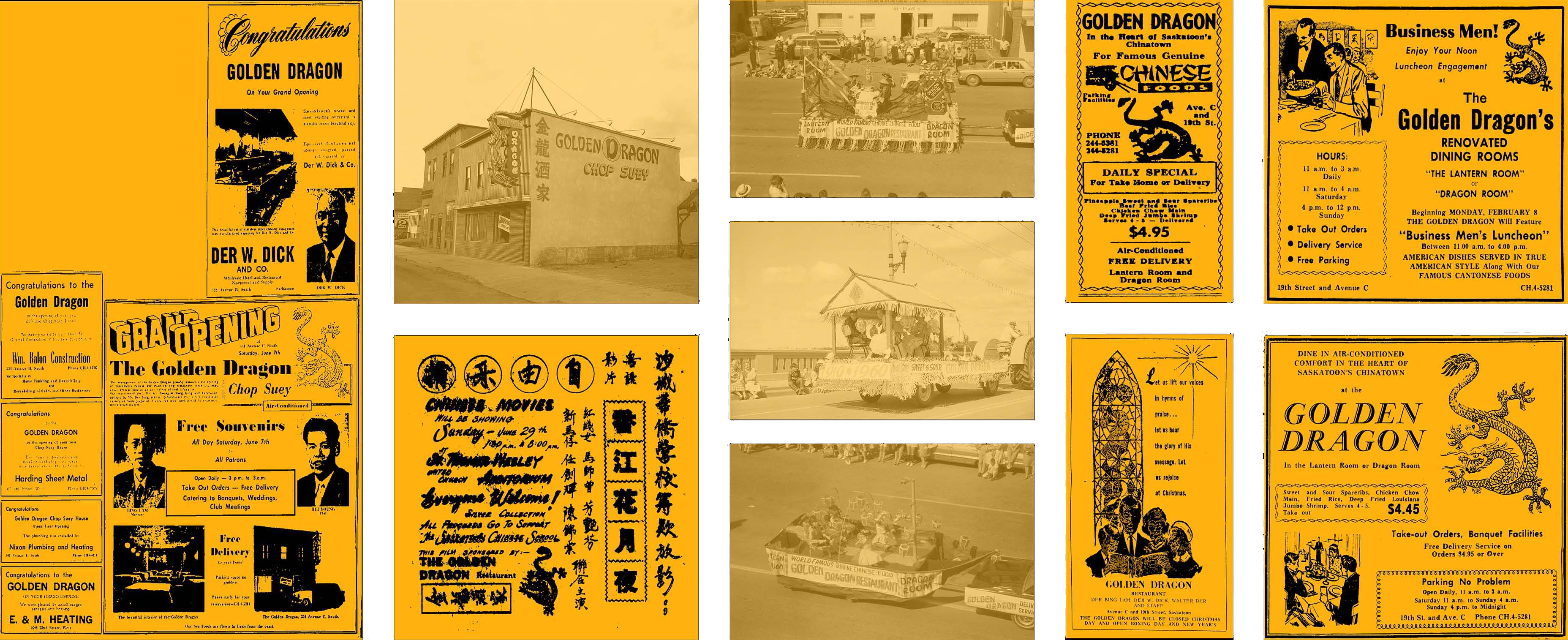

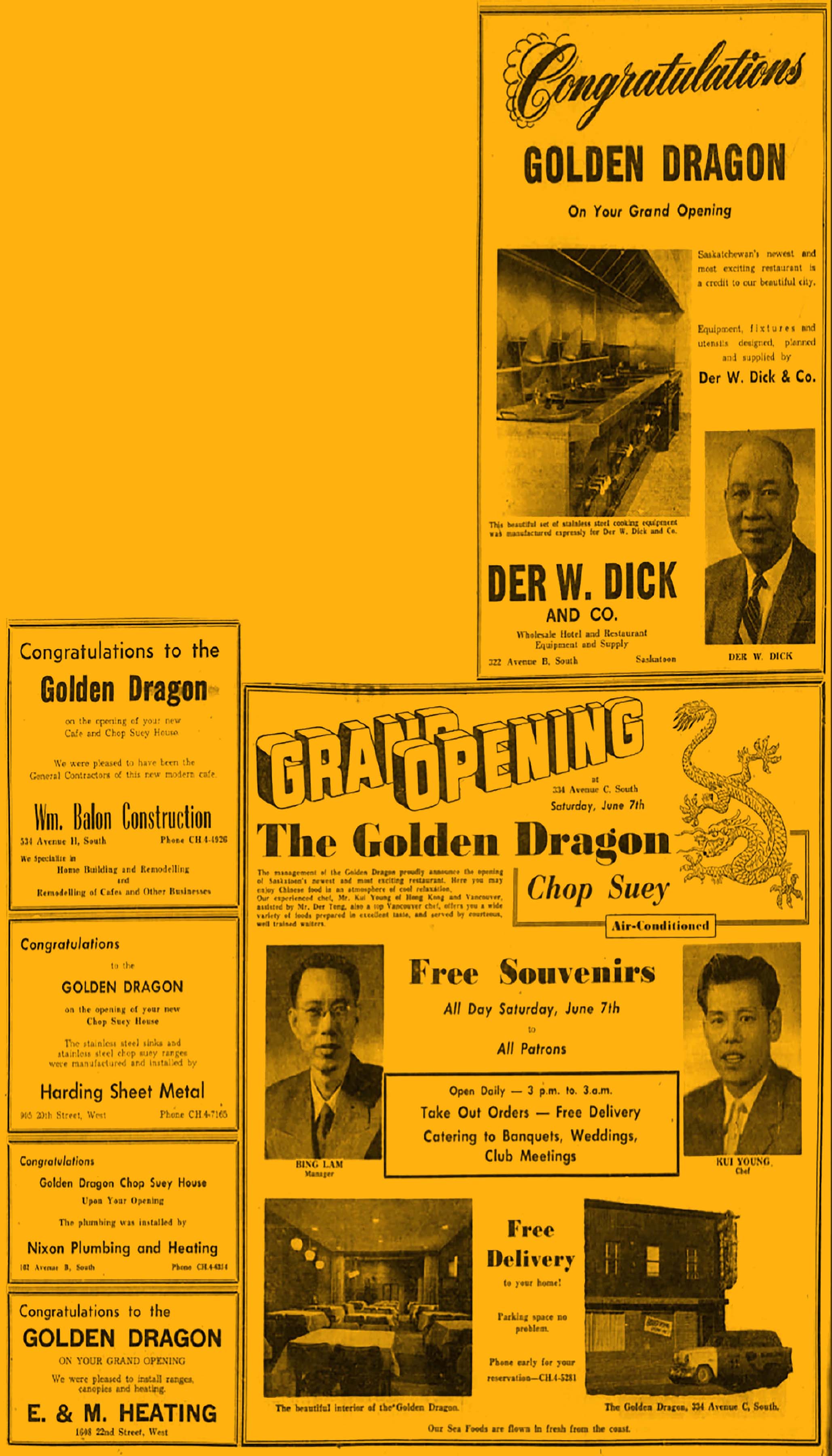

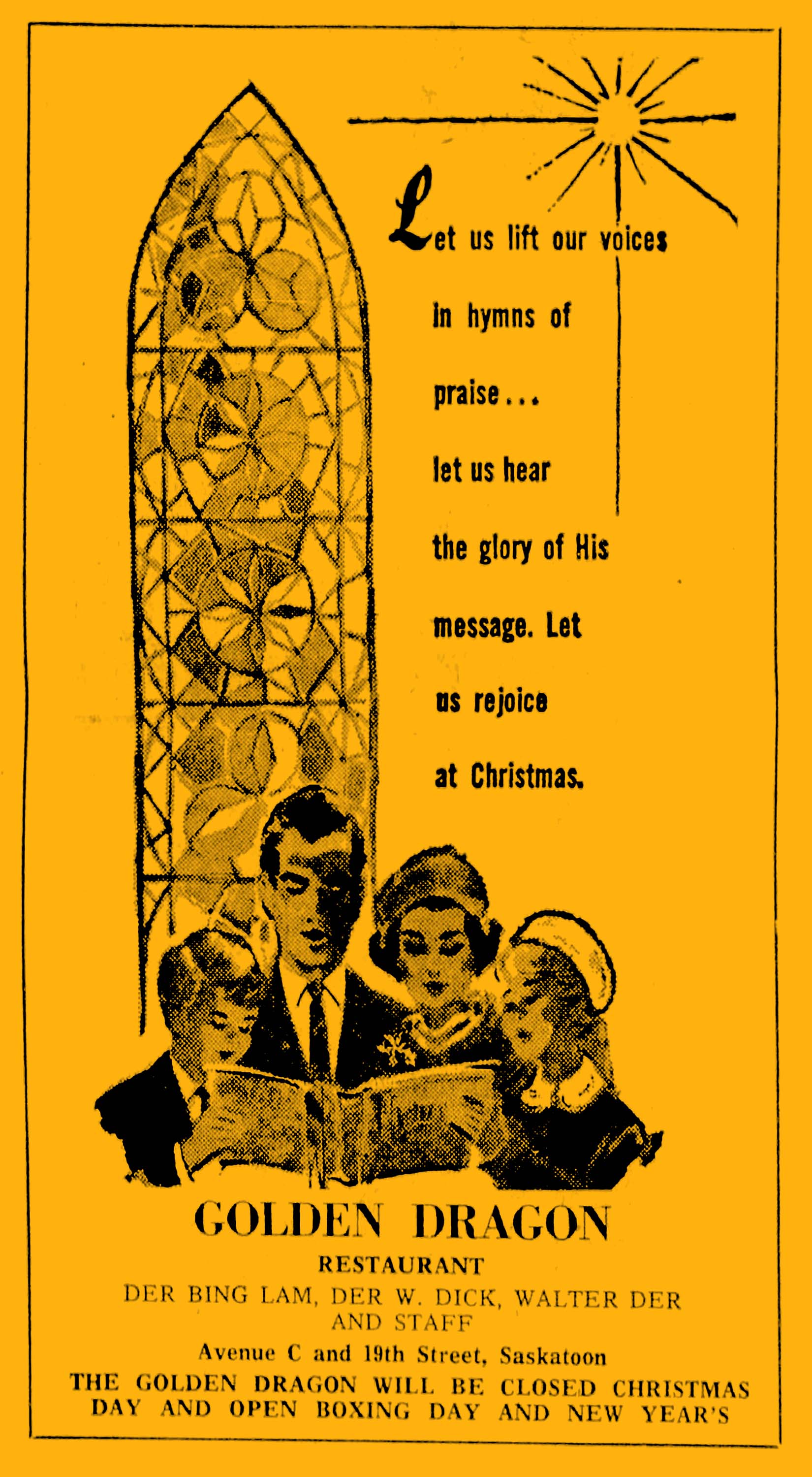

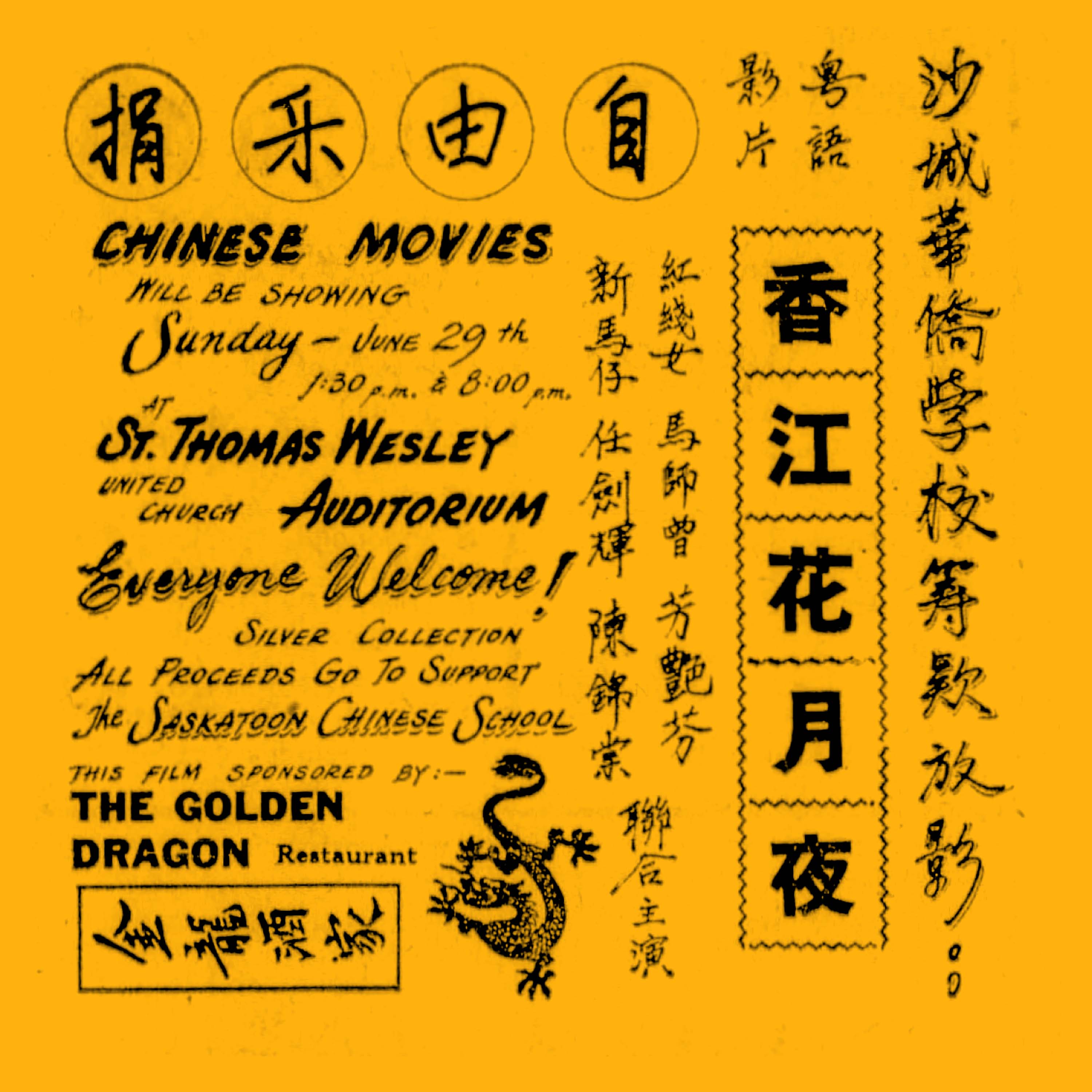

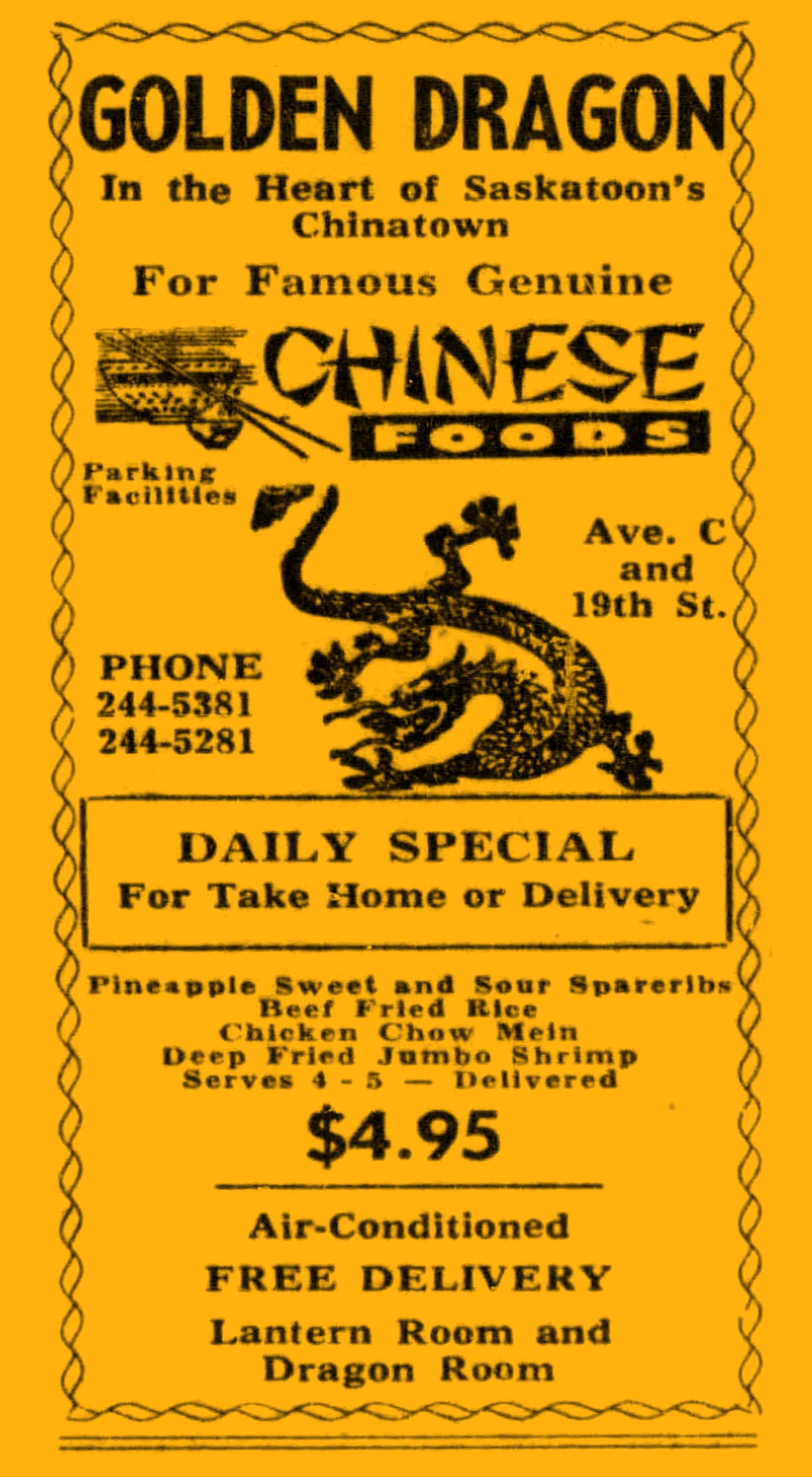

In 1958, the Golden Dragon restaurant opened on 334 Avenue C in Saskatoon. Three partners, brothers Bing and Walter Lam Der, and Der W. Dick, ran the restaurant together. Bing and Walter came to Canada from Canton. In 1958, they joined Der, a local businessman who was in the restaurant supply business. This location would be part of the city’s “new Chinatown” which saw new businesses emerging in the area after the repeal of the Chinese Immigration Act. Previously, the building was home to another long-standing Chinese restaurant named the Nanking Chop Suey. The Dick family lived close to the restaurant in a tight knit community along 20th Street. Many Chinese newcomers who worked in the kitchen lived in a rooming house that was separated from the restaurant by a parking lot.

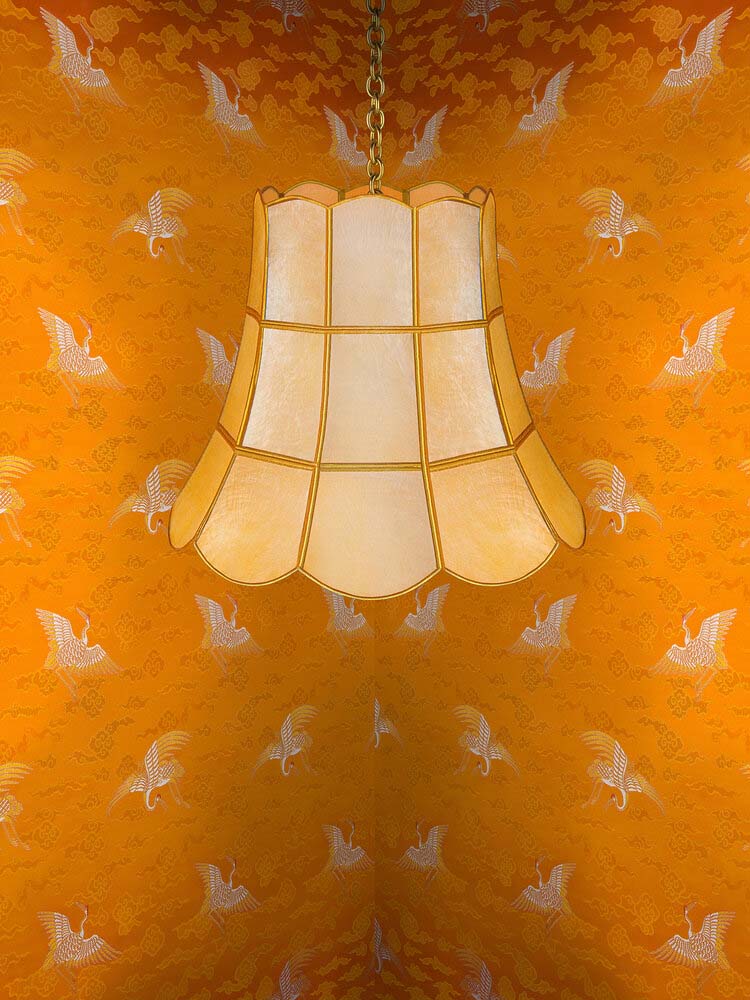

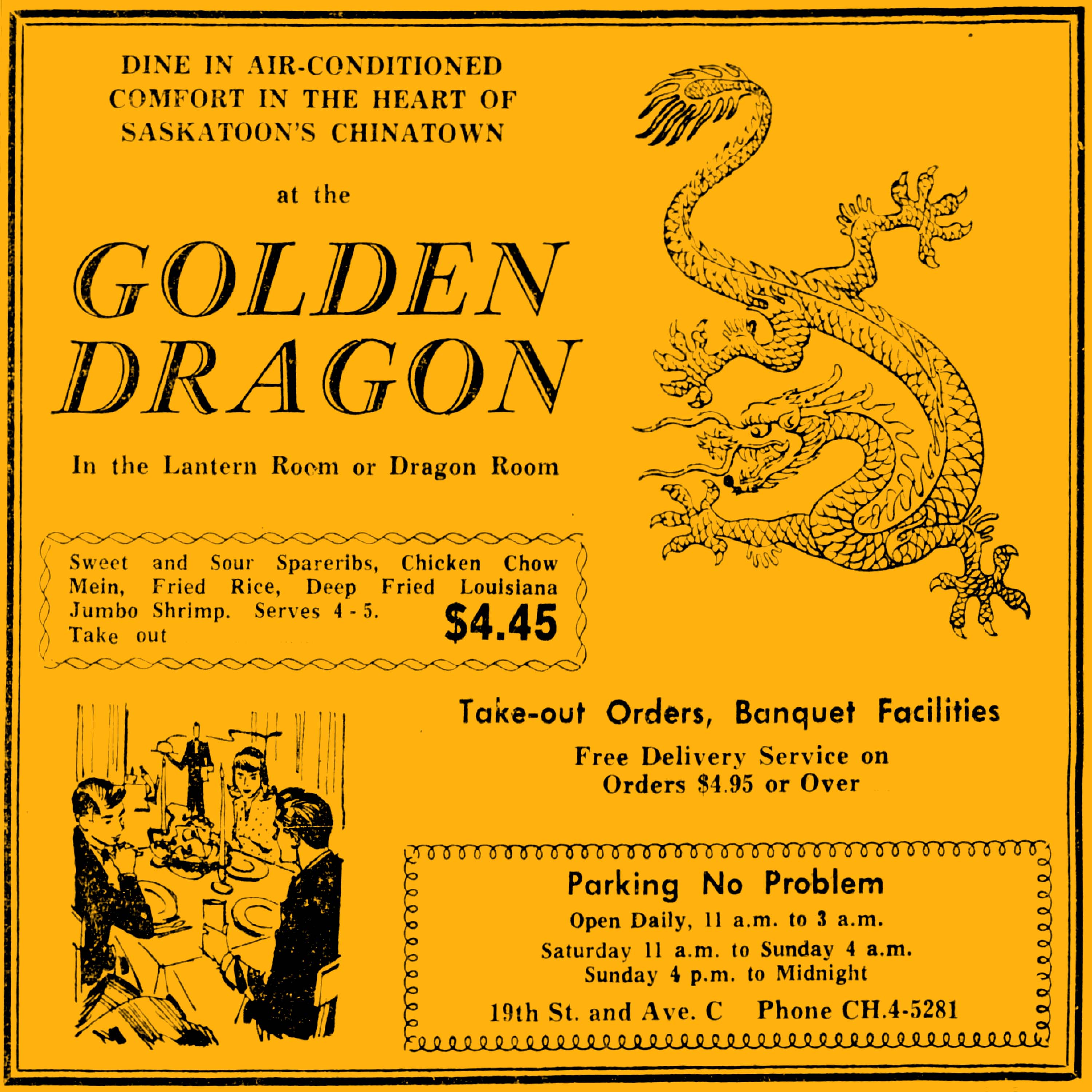

The Golden Dragon restaurant was an upscale venue serving chop suey cuisine where visitors would come for special occasions or a late night drink. Inside, the restaurant was decorated with orange vinyl chairs, silk crane wallpaper, white tablecloths and lanterns strung from the ceiling—most of which were imported directly from China. A small Chinese architecture-style roof covered a bar which served a generous menu. Downstairs, the restaurant would grow their own bean sprouts in baskets in the basement. Outside, the restaurant was lit by an iconic dragon neon sign. The restaurant advertised itself by promoting its Lantern and Dragon rooms, banquet facilities, take out menu and parking space. They would also be frequent participants in the city’s Travellers’ Day Parade with floats that mimicked the memorable aspects of the restaurant’s décor. A notable shift from past generations of Chinese restaurants was the Golden Dragon’s ability to market itself as a stylish and hospitable venue that could cater to various engagements ranging from family dinners to businesses meetings, while earlier restaurants in Chinatown were overwhelmingly burdened by the conception of Chinatown as an unclean and unsafe place.

In 2011, a restaurant named The Hollows focused on farm-to-table dining leased the Golden Dragon space and kept the majority of the former restaurant’s décor. In 2020, fire inspectors and the city called for updates to the building structure in order to bring it up to code. The current owners decided against this costly investment and opted to tear it down instead. Objects and fixtures from the restaurant were auctioned off and on November 27, 2020, the building was demolished.

Exterior of Building Ca. 1960 Photographer CFQC Staff Saskatoon Public Library. Call number QC-912.

Golden Dragon Grand Opening Saskatoon Star-Phoenix June 6, 1958 Accessed from Newspapers.com

Golden Dragon Ad Saskatoon Star-Phoenix June 6, 1960 Accessed from Newspapers.com

Golden Dragon Ad Saskatoon Star-Phoenix January 21, 1961 Accessed from Newspapers.com

Golden Dragon Ad Saskatoon Star-Phoenix December 24, 1963 Accessed from Newspapers.com

Golden Dragon Ad Saskatoon Star-Phoenix June 28, 1969 Accessed from Newspapers.com

Golden Dragon Ad Saskatoon Star-Phoenix October 3, 1964 Accessed from Newspapers.com

Parade float promoting the Golden Dragon Restaurant July, 1960 Photographer: Hillyard, Leonard A. Saskatoon Public Library. Call number. B-7855

Golden Dragon Restaurants’ float 1963 Photographer: Penkala, J. Saskatoon Public Library. Call number. LH-4298-3

Decorated “Golden Dragon Restaurant” float 1965 Photographer: Arling, Ted Saskatoon Public Library. Call number. PH-2016-64-25.